1. How did the most extreme skeptics (or sceptics, if you prefer the British spelling) differ from Plato and Aristotle? What was their main teaching? Do you think they were "Socratic" in this regard?

2. Why did Pyrrho decide never to trust his senses? Is such a decision prudent or even possible?

3. What country did Pyrrho visit as a young man, and how might it have influenced his philosophy?

4. How did Pyrrho think his extreme skepticism led to happiness? Do you think there are other ways of achieving freedom from worry (ataraxia)?

5. In contrast to Pyrrho, most philosophers have favored a more moderate skepticism. Why?

FL

1. What did Anne Hutchinson feel "in her gut"? What makes her "so American"?

2. What did Hutchinson and Roger Williams help invent?

3. How was freedom of thought in 17th century America expressed differently than in Europe at the time?

4. Who, according to some early Puritans, were "Satan's soldiers"? DId you know the Puritans vilified the native Americans in this way? Why do you think that wasn't emphasized in your early education?

5. What extraordinary form of evidence was allowed at the Salen witch trials? What does Andersen think Arthur Miller's The Crucible got wrong about Salem?

HWT

1. Logic is simply what? Do you consider yourself logical (rational)?

2. What "law" of thinking is important in all philosophies, including those in non-western cultures that find it less compelling? Do you think it important to follow rules of thought? What do you think of the advice "Don't believe everything you think?"

3. For Aristotle, the distinctive thing about humanity is what? How does Indian philosophy differ on this point? What do you think is most distinctive about humanity?

4. According to secular reason, the mind works without what? Are you a secularist? Why or why not?

5. What debate reveals a tension in secular reason? How would you propose to resolve the tension?

And see:

==

==

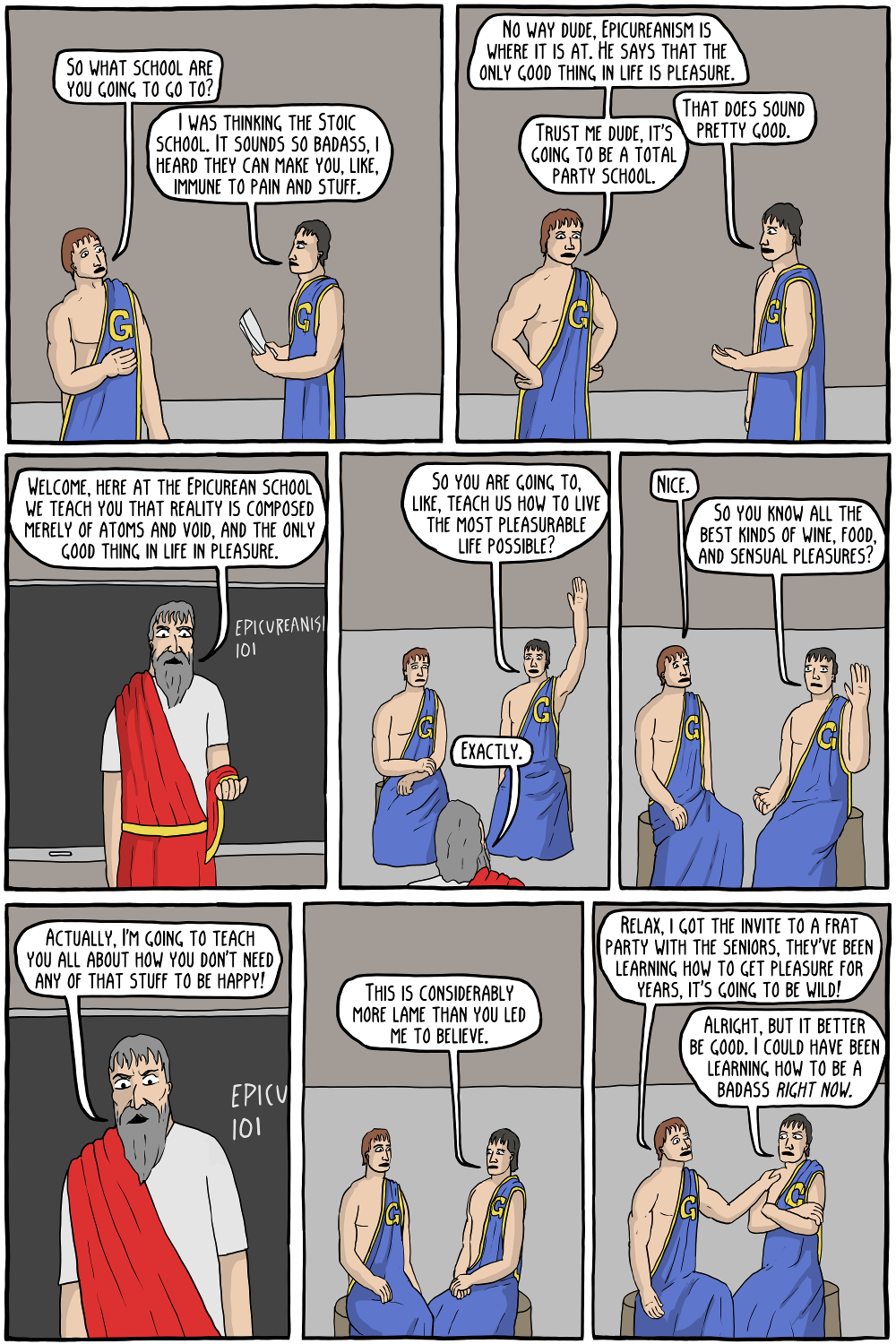

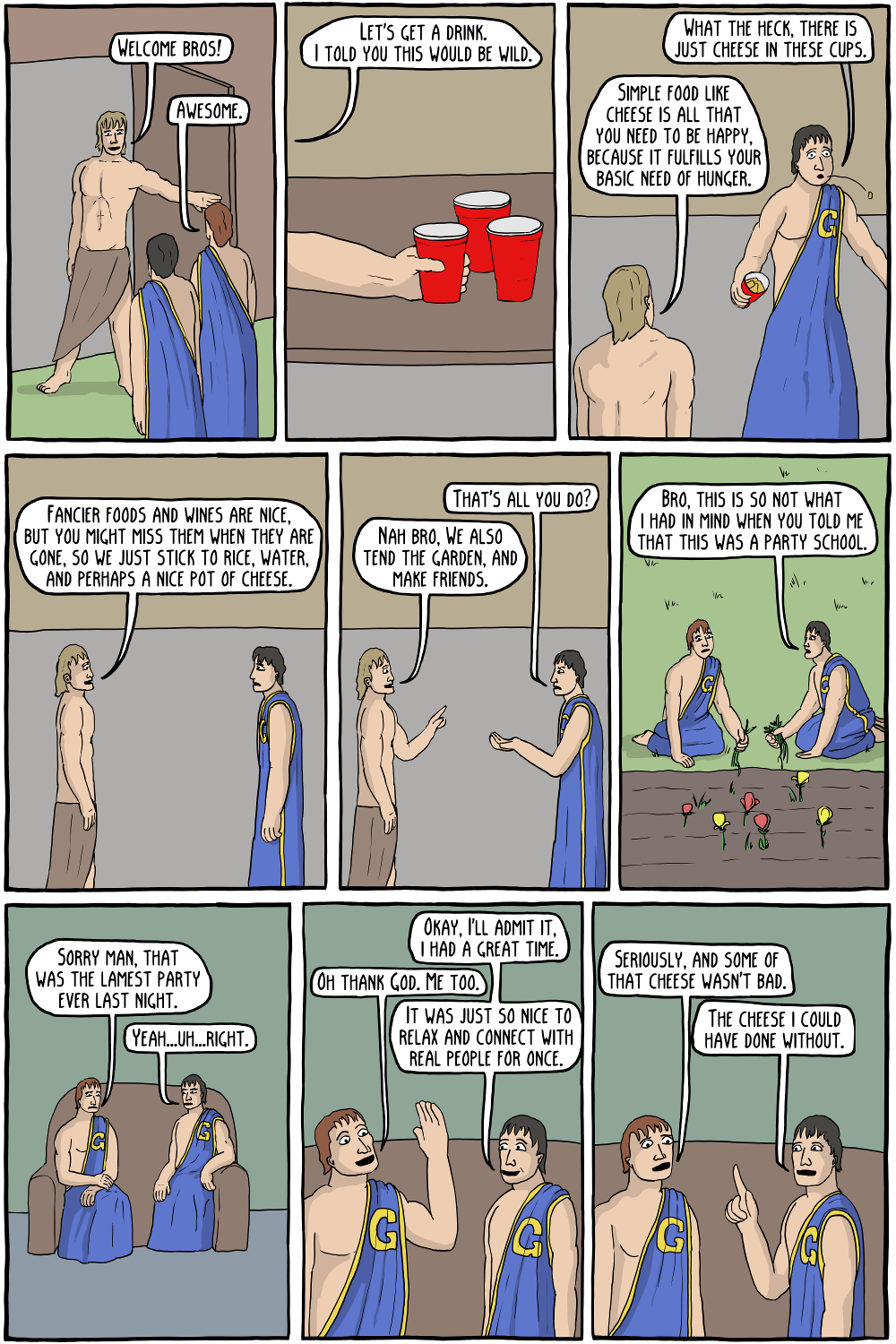

Pyrrho was an extreme skeptic, who'd abandoned the Socratic quest for truth in favor of the view that beliefs about what's true are a divisive source of unhappiness. But most philosophers do consider themselves skeptics, of a more moderate strain.

The difference: the moderates question everything in order to pursue truth, knowledge, and wisdom. They're skeptical, as Socrates was, that those who think they know really do know. But they're still searching. Pyrrhonists and other extreme ancient skeptics (like the Roman Sextus Empiricus) find the search futile, and think they can reject even provisional commitment to specific beliefs.

My view: we all have beliefs, whether we want to admit it or not. Even those who deny belief in free will, it's been said, still look both ways before crossing the street.

So let's try to have good beliefs, and always be prepared to give them up for better ones when experience and dialogue persuade us we were mistaken.

==

It's hard to take the legend of Pyrrho seriously.

"Rather appropriately for a man who claimed to know nothing, little is known about him..."*

Pyrrho

First published Mon Aug 5, 2002; substantive revision Tue Oct 23, 2018

Pyrrho was the starting-point for a philosophical movement known as Pyrrhonism that flourished beginning several centuries after his own time. This later Pyrrhonism was one of the two major traditions of sceptical thought in the Greco-Roman world (the other being located in Plato’s Academy during much of the Hellenistic period). Perhaps the central question about Pyrrho is whether or to what extent he himself was a sceptic in the later Pyrrhonist mold. The later Pyrrhonists claimed inspiration from him; and, as we shall see, there is undeniably some basis for this. But it does not follow that Pyrrho’s philosophy was identical to that of this later movement, or even that the later Pyrrhonists thought that it was identical; the claims of indebtedness that are expressed by or attributed to members of the later Pyrrhonist tradition are broad and general in character (and in Sextus Empiricus’ case notably cautious—see Outlines of Pyrrhonism 1.7), and do not in themselves point to any particular reconstruction of Pyrrho’s thought. It is necessary, therefore, to focus on the meager evidence bearing explicitly upon Pyrrho’s own ideas and attitudes. How we read this evidence will also, of course, affect our conception of Pyrrho’s relations with his own philosophical contemporaries and predecessors... (Stanford Encyclopedia, continues)

==

"Pyrrho ignored all the apparent dangers of the world because he questioned whether they really were dangers, ‘avoiding nothing and taking no precautions, facing everything as it came, wagons, precipices, dogs’. Luckily he was always accompanied by friends who could not quite manage the same enviable lack of concern and so took care of him, pulling him out of the way of oncoming traffic and so on. They must have had a hard job of it, because ‘often . . . he would leave his home and, telling no one, would go roaming about with whomsoever he chanced to meet’.

Two centuries after Pyrrho’s death, one of his defenders tossed aside these tales and claimed that ‘although he practised philosophy on the principles of suspension of judgement, he did not act carelessly in the details of everyday life’. This must be right. Pyrrho may have been magnificently imperturbable—Epicurus was said to have admired him on this account, and another fan marvelled at the way he had apparently ‘unloosed the shackles of every deception and persuasion’. But he was surely not an idiot. He apparently lived to be nearly ninety, which would have been unlikely if the stories of his recklessness had been true."

"The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance by Anthony Gottlieb -- a very good history of western philosophy.

==

A character in Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, identified as The Ruler of the Universe, has been called a solipsist. I think he sounds more like a Pyrrhonian skeptic... "I say what it occurs to me to say when I hear people say things. More I cannot say..."