UPDATE, March 15. Great meeting you all last night, you're an eclectic cohort!

Following up on some of last night's discussion...

Another ancient skeptic like Pyrrho... What do we know about time?... Would you not prefer to take the red pill and live by the truth, warts and all?... Aldous Huxley on the difference between knowledge and understanding... “The reading of all good books is like a conversation with the finest minds of past centuries.” — René Descartes (at least he got that right!)...

I asked my friend Ed what he'd tell you all about knowledge and philosophers:

Ed: I’d start with some basics. First, that Western philosophy began with a bunch of Greeks being curious about knowing the nature of the world through experience and not just accepting mythological answers. Philosophy began in wonder. They sought the truth of things. That led to the sciences, through which we know things, until we know otherwise. It led to epistemology, a whole field of thinking about the nature of knowledge. Then I’d give a little lecture on The Will to Believe, and talk about the difference between opinion and truth, and how opinion can become truth. I’d end by discussing the major problem we face today, which is that we are awash in disinformation, and too many of us just accept assertions without ever seeking the truth. We think we know something just because we heard someone say it. Knowledge is the result of truth-seeking. Philosophers, like Spinoza, teach us that the truth will set us free. We need to always ask ‘how do you know that and how do you know that it’s true’, especially, and unfortunately, our lawmakers.

A couple of things I believe, try to act on, and would claim to "know" in a pragmatic sense--we'll talk about what that means--based on my experience of so acting:

- I agree with Montaigne that a cheerful humility is better than arrogant pessimism. "The most certain sign of wisdom is cheerfulness”

- Emerson's advice to his daughter was golden: resist perfectionism. He wrote a letter to his daughter: “Finish each day and be done with it. You have done what you could. Some blunders and absurdities no doubt crept in; forget them as soon as you can. Tomorrow is a new day. You shall begin it serenely and with too high a spirit to be encumbered with your old nonsense.”

==

UPDATE, March 9: Post your assignment responses in the comments section below. The first 47 responses are those of your predecessors in this course last September.

==

The theme this semester is Knowledge... My block, Knowledge and Philosophers, is Sep 7 & 14 March 14 & 21.

FIRST ASSIGNMENT Sep 7 March 14: Before class, read at least four of the following chapters in A Little History of Philosophy: ch 1-Socrates/Plato, 2-Aristotle, 3-Pyrrho, 11-Descartes, 14-Locke, 17-Hume, 19-Kant, 23-Schopenhauer, 39-Turing/Searle. Before OR after class, go to the comments section below this post and pose, then answer, at least two discussion questions inspired by what you've read. ALSO RECOMMENDED: read as many of the posted and linked articles below as you'd like, and share your thoughts in the comments space.

SECOND ASSIGNMENT Sep 14 March 21: Before class, read in A Little History of Philosophy: ch 28-Peirce and James; and Pragmatism I, II, VI (or as much as you can manage)... Also recommended, James's "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings"... Before OR after class, go to the comments section below this post and pose, then answer, at least two discussion questions inspired by what you've read. And again, ALSO RECOMMENDED: read as many of the posted and linked articles below as you'd like, and share your thoughts in the comments space. ALSO RECOMMENDED: the SEP entry on Pragmatism...

Title: Knowledge and Philosophers

Block Description: Philosophers in every tradition have pondered the meaning and purpose of knowledge, and whether that can even be adequately expressed in words and concepts. Some relatively-recent epistemologists (theorists of knowledge) have treated this as an arcane and technical subject. Mystics have deemed reality itself ineffable (literally unspeakable), even if in some inward sense knowable. In the western tradition, ancient pre-Socratic philosophers proposed alternative possibilities for knowing the world and our place in it (Democritus, for instance, was an early atomist insisting that all there is and (thus) all we can know is material. Later, Plato and other rationalists held that knowledge must transcend the material (“visible”) world. His student Aristotle disputed that. Later still, Descartes contradicted his French predecessor Montaigne in holding that absolute “indubitable” knowledge is possible and desirable. Scottish empiricist David Hume was skeptical of knowledge. Immanuel Kant thought he’d solved the question in terms of what he called a Copernican revolution, cautioning against trying to know reality-in-itself. His German idealistic successors Hegel, Schopenhauer, and others ignored that caution. More recently in America, pragmatists William James, John Dewey, Richard Rorty and others have understood “knowing the world as inseparable from agency within it.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). We’ll discuss what this all might mean, and why it matters.

Week 1 Readings/assignments: post responses to at least two discussion questions

Week 2 Readings/assignments: post responses to at least two discussion questions

Grade Distribution: Participation (including posted responses) 50% each week

==

"Knowledge" quotes...

==

To George Santayana.

Orvieto, May 2, 1905.

Dear Santayana,—I came here yesterday from Rome and have been enjoying the solitude. I stayed at the exquisite Albergo de Russie, and didn't shirk the Congress—in fact they stuck me for a "general" address, to fill the vacuum left by Flournoy and Sully, who had been announced and came not (I spoke agin "consciousness," but nobody understood) and I got fearfully tired. On the whole it was an agreeable nightmare—agreeable on account of the perfectly charming gentillezza of the bloody Dagoes, the way they caress and flatter you—"il piu grand psicologo del mondo," etc., and of the elaborate provisions for general entertainment—nightmare, because of my absurd bodily fatigue. However, these things are "neither here nor there." What I really write to you for is to tell you to send (if not sent already) your "Life of Reason" to the "Revue de Philosophie," or rather to its editor, M. Peillaube, Rue des Revues 160, and to the editor of "Leonardo" (the great little Florentine philosophical journal), Sig. Giovanni Papini, 14 Borgo Albizi, Florence. The most interesting, and in fact genuinely edifying, part of my trip has been meeting this little cénacle, who have taken my own writings, entre autres, au grand sérieux, but who are carrying on their philosophical mission in anything but a technically serious way, inasmuch as "Leonardo" (of which I have hitherto only known a few odd numbers) is devoted to good and lively literary form. The sight of their belligerent young enthusiasm has given me a queer sense of the gray-plaster temperament of our bald-headed young Ph.D.'s, boring each other at seminaries, writing those direful reports of literature in the "Philosophical Review" and elsewhere, fed on "books of reference," and never confounding "Æsthetik" with "Erkentnisstheorie." Faugh! I shall never deal with them again—on those terms! Can't you and I, who in spite of such divergence have yet so much in common in our Weltanschauung, start a systematic movement at Harvard against the desiccating and pedantifying process? I have been cracking you up greatly to both Peillaube and Papini, and quoted you twice in my speech, which was in French and will be published in Flournoy's "Archives de Psychologie." I hope you're enjoying the Eastern Empire to the full, and that you had some Grecian "country life." Münsterberg has been called to Koenigsberg and has refused. Better be America's ancestor than Kant's successor! Ostwald, to my great delight, is coming to us next year, not as your replacer, but in exchange with Germany for F. G. Peabody. I go now to Cannes, to meet Strong, back from his operation. Ever truly yours,

WM. JAMES.

The Edge of Knowledge

by Grant Bartley

Epistemology is the mining boss of philosophy. It digs deep into the foundations even of philosophy itself. The word means the study of knowledge (from the Greek episteme meaning ‘knowledge’ or ‘belief’, or in some circles, ‘faith’.) Its question is, How can we be sure about anything?

René Descartes asked this question in its most radical form when he said: if a powerful, evil demon set out to mislead us about everything, then how could we tell? If we couldn’t tell, how do we know that there really isn’t such a demon?

Less generally, how can you ever credibly claim to know something before you can say how you know it? Put this way, it’s not hard to see that epistemology is at the base of science, philosophy, religion and many other areas of human endeavour. But the ways we know things may differ from field to field.

How do we know when a theory is scientifically valid? Here, what we want to know is whether it is an accurate description of the world, within its limits. The methodology of science is to compare the theory with whatever it is that the theory is about, then refine the theory as necessary until it gives a description consistent with what is observed. (As to which theories are scientific, a set of possible criteria is proposed by Russell Berg on p.14.) Science is about the observed world. The principle of how we know something to be true in science is, we know this is the way the observed world behaves because this is how it may best (ideally, incontrovertibly) be observed to behave.

Maths proofs are good for maths. In an attempt to uncover a general pattern for knowledge, perhaps we could redescribe the process of mathematical discovery so that it too could be thought of as comparing a theory to what that theory is about. Here the evidence for the conclusion would be the steps it takes to get there. Similarly for arguments of logical symbolism: the evidence would be the steps in the argument. Thus what counts as evidence would be different for different domains, evidently. (Philosophy doesn’t count as purely logical, because as soon as signs are used as language, possible meanings for each sign multiply exponentially. Peter Rickman argues that psychology cannot be considered science for this precise reason.)

Aside from the incontrovertible parts of science, maths and logic, can any other way of thinking strictly be called ‘knowledge’ – that is, yielding an assurance of truth? Could there be ways to what might rightly be called knowledge concerning religious experience, emotional intuitions, philosophical ideas too? Why/why not? (And which way? Kile Jones reports on the split between analytical and continental philosophy in thought and method.) To say that ‘religious experience’ for instance is inadmissible as evidence begs the question of what is admissible. However, the enquirer should also ask why and which religious experience is admissible. Why trust this type? The unflinching claim to know something without the willingness (or ability) to respectably say how, is the most philosopher-baiting aspect of dogmatism. The core impulse of reason, the demand for understanding, requires openness to all questions, especially concerning how ideological claims to knowledge are justified, because of the significant implications of these claims. On the other hand, a sceptic’s lack of imagination is not necessarily the same as a discernment of truth. We look at religious knowledge-claims from both sides in the book reviews section of this issue.

Even if in the less provable areas we can’t have what could strictly be called knowledge, in the sense of ‘incontrovertible assurance’, so what? Doesn’t the question of what to believe in these situations simply soften into ‘What’s the most reasonable thing to believe?’ This will not satisfy the truly paranoid Cartesian, but scepticism to the extent that we can’t trust anything we can’t incontrovertibly demonstrate, is only really useful as an exercise in delimiting the borders of certainty. Nevertheless, it’s a paradox of philosophy, or at least an irritation, that you can’t often prove philosophical views; you can only give your best reasons to support them – and these are only the reasons you’re prepared to settle for… On the bright side the acknowledgement of fallibility can have a moderating effect on the passions of zealotry. As with anything, the claims of any religion are only as justified as the best reasons to believe they’re true – yet a wider appreciation of this fact this might just take the edge off the absolute justification of idiotic and barbaric acts in the name of The Truth.

The value of a good philosophy of knowledge can be seen in all the fruits of science. Thus, contrary to Descartes’ mental quicksand, and in the face of the fears of all who do not trust questioning – who fear their belief-systems might be undermined by too many questions – we can view the epistemological mission as benevolent: to increase the stock, strength and detail of our most reasonable beliefs by providing them with the strongest foundation of justification possible; and perhaps to open up new ways of knowing. Engaging the epistemological understanding which is the touchstone of scientific research was like stepping into a hidden grotto universe. Who knows what knowledge is possible if we find equally good ways of knowing for other areas of enquiry too?

Grant Bartley is Assistant Editor of Philosophy Now. His book The Metarevolution is available as a free download from philosophynow.org.

==

Knowledge & Reasons

Joe Cruz gives an evolutionary account of them.

Epistemologists are philosophers who seek to understand what knowledge is, whether we have any of it, and whether, perhaps, we can improve our ability to gain more of it. ‘Knowledge’ is understood here in a general sense. Particular bits of knowledge – for instance, knowing that 7+5=12, or how to knit mittens, or that George Washington was the first President of the United States – are treated as data. Epistemologists ask, what makes possession of each of those bits of data instances of knowledge, as opposed to merely opinion?

There is a difference between having knowledge and merely having an opinion even if the opinion is correct or useful. After all, one could have a true opinion accidentally, by, say, correctly guessing. If I am lost at a fork in the road and flip a coin to decide which way to go, it may turn out that the opinion I form leads me to where I wanted to go. Still, I did not know that going left was correct, even though it was. So being true does not by itself make a belief properly knowledge – although most philosophers think that being true is a necessary condition for knowledge. Moreover, having opinions, even useful, true ones, does not tell us what procedure to employ to get new useful, true beliefs. Opinions are in a sense inert. By their nature, mere opinions are arrived at in a way that is uncertain and obscure. It is only by understanding knowledge, epistemologists think, that we can obtain an intellectual procedure with which we can move forward . So epistemologists set out to determine what is needed to make the difference between a true opinion and knowledge.

One natural thing to think, is that in addition to being true or useful, knowledge requires having good grounds, reasons or evidence for what is known. This is what was missing in the coin flip at the fork in the road: I had no reason to think left was correct, even if it turned out to be. Knowledge and rationality therefore seem intimately connected, in that having knowledge requires good reasons, and being rational is the process of employing good reasons. Epistemology has thus expanded to include the study of the rationality or reasonableness of beliefs, and it has done so in a way that suggests a close relationship between knowledge and rationality.

Reasoning About Reasons

Unfortunately, the introduction of the need for good reasons trades one mystery for another. What makes some reasons good and other reasons bad? To answer this question epistemologists will need to give an explanation of what features any reason has to have in order to be good.

Certain kinds of answers to this question are tempting but probably cannot give a fully general theory of good reasons. For instance, mathematicians have a decent grip on what counts as a good reason in a mathematical proof: a reason is good in mathematics if it is sanctioned by the rules of the formal system in question. So it is reasonable to believe that 7+5=12 – in fact, we may even know it – because the answer is determined by the rules of arithmetic within a fixed notation system. But this does not provide a general answer to the question of good reasons, because most areas of thought do not have tightly-defined rules and fixed meanings of the mathematical sort. Still, the mathematical case might be illuminating. What is promising about it is that there is an acceptable starting point for good mathematical reasoning – the axioms – and an acceptable procedure for drawing conclusions – the rules. If there is something like that in the non-mathematical domains, then we might be in a better position to understand good reasons both in ordinary life and in science.

Historically, and intuitively, perception has seemed a good starting point for forming rational beliefs. If someone sees or hears or otherwise perceives something, we think that generally, that is an acceptable basis for her to form beliefs about that thing, and for those beliefs consequently to be rational. To be sure, there are instances where we would not think this. If someone has reason to suspect that her perceptual experience is distorted or otherwise unreliable, then we would not think that her beliefs formed on the basis of that perception are reasonable. But generally as a starting point, it seems that perception is an acceptable basis for forming rational beliefs. Of course, to be reasonable, those beliefs have to be about the thing perceived. If I see a chair in front of me, that is not by itself a good reason to believe that George Washington was the first President of the United States. Even bringing up George Washington is absurd, because the US presidency has nothing to do with chairs – barring some convoluted and circuitous connection that would need to be spelled out.

This gives us some sense, then, of the rules that govern the formation of rational beliefs on the basis of perception: (pending some good reason to think otherwise) if someone forms a belief on the basis of the perceptions she has, and the belief is about the perceived properties of the thing, beliefs so formed are rational. The model of rationality suggested by mathematics, that is, the idea of having a fixed starting point and having rules that determine what beliefs are acceptable to form on the basis of that starting point, has now been applied by analogy to a non-mathematical domain. Many epistemologists think that, if a similar account can be given for a range of beliefs that are not about perception – for example, ones about memory or testimony or probability – then we will have made headway on the main project of epistemology, to account for knowledge generally.

Problems With Reasons

There is an important wrinkle in this theory of good reasons. It is ambiguous to whom the reasons have to be good in order for beliefs formed on their basis to be rational. That is to say, my belief may be rational to some third party if they were to examine it, but if I myself do not appreciate the reasons for it, it is plausible to say that I am not rational in believing it. Imagine that I complete a maths quiz by fudging some steps. I have no idea whether the steps are legitimate, but suppose, unbeknownst to me, I accidentally get those steps right. Even though my conclusions are correct, they are not rational, because I did not appreciate the good reasons leading to the conclusion. Rationality thus appears to have a strong first-person dimension, in that the believer must possess the evidence and the rules for drawing rational conclusions herself, and must in some way appreciate that fact as she applies the rules.

There will be many ordinary cases where a person does not have a particularly good grasp on the reasons for a belief she has. She may have forgotten her reasons, but still feel fairly confident in the belief. Or she might recognize her reasons, but not be able to articulate what makes those reasons good. If cross-examined by a skeptic, she may be unable to defend herself.

If confronted by a very persistant skeptic, to uphold her rationality a person may need to say not only what her good reasons are for believing that the reasons she has are good, but what her good reasons are for believing that those underlying reasons are good, and so on. No one can give good reasons for good reasons for good reasons indefinitely, so for it to be possible for anyone to be rational, there must exist legitimate stopping points in reason-giving. One need not even be able to get back to those stopping points in every case. At the very least, however, we expect a person to be able, if allowed time and patient reflection, to recover in some way what her reasons for her beliefs are, and very broadly, why they are good ones.

Here is where we are so far. In order to be knowledge, a belief has to be true and based on good reasons for it. Good reasons are different from bad reasons in that good reasons can be traced to some source such as perception that keeps us connected with the thing that we form the belief about.

These modest bits of progress can certainly be challenged and rejected, and, even if they are right, they invite a dizzying list of further questions. Contemporary epistemology is largely an attempt to give reasoned, systematic answers to such questions. But we should notice that as interesting, challenging, and worthy as it is, this agenda of refining this framework of epistemology is something akin to writing the final chapter in a much broader epistemological narrative. It is equally important to see how philosophers conceive of the even bigger picture: How is it that the capacity to know things is present in human beings? What makes knowledge possible at all? This is the question I want to address in the rest of this article.

The Automatic Behavior of Living Things

Nonliving things remain what they are because they passively resist forces that would compromise their integrity and persistence. (By ‘integrity’, I mean being a thing staying together spatially, and by ‘persistence’, I mean a thing with a continuous intelligible nature enduring over time.) By contrast, the persistence and integrity of living things is achieved actively – by their doing something to adapt to their environments; to respond to challenges or to change their environment to increase their favorability.

The distinction between passive and active here is metaphysically problematic. What could it mean to say that some things ‘don’t do’ and some things ‘do’? In a sense, everything does as it does. We see the strain involved in making the distinction between non-living and living things, and therefore between passive and active, in, for example, viruses. However, scientists are not usually vexed about the definition of the boundary. Instead, scientists mark the distinction by offering different ways of thinking about nonliving and living things. The central domain of inorganic chemistry is nonliving things, while the central domain of biology is living things. The border cases provide fascinating and lively areas of scientific inquiry. Organic chemistry can be viewed as a science of the border cases that forms a bridge between understanding the nonliving and the living. It’s a good thing, since it shows that explanations at various levels of analysis can be reconciled, by saying that biological things are made of chemical things that are in turn made of physics things.

Let us use the explanatory (as opposed to the metaphysical) sense of the ‘passive’ versus ‘active’ distinction to sharpen our broader epistemological picture. Consider the contrast between rocks and ants. Rocks have a physical nature (eg, their solidity) that passively preserves what they are against many kinds of influences in the world. There are some changes that rocks cannot retain their integrity and persistence against, such as an earthquake or the flow of a river, and so rocks might be transformed into something else passive, like dust. For a span, however, rocks are what they are because of a fixity that passively resists change. The vast majority of things in this universe seem to stay what they are in the same sort of way.

Ants are different. They actively cause changes in their environment in order to maintain a certain equilibrium with that environment. They engage in adaptive, effortful activity to preserve their nest, for example. Ants have a fixed nature too, but this nature has a different character to that of rocks. Rocks are persistent wholly in virtue of a relatively static structure, whereas ants wouldn’t remain the same unless they could change. An ant is an organism evolved to intervene actively ‘on its own behalf’, and it does so by dint of the flexible arrangement of its parts. Ants’ parts self-organize, shifting their relationships to one another. It looks like this activeness disappears under analysis, since it seems like it’s achieved through the complex interaction of parts that are individually passive. So the physical makeup of ants, like that of all living things, possesses a fundamental passive integrity that in other respects allows them to be active. However, let us focus on the active aspect of organisms.

“I don’t know what I’m doing!” “No, neither do I!”

© istockphoto.com/Antrey

What is the source or director of activity in living things that are automatic in their behavior, as ants are? This is not a great mystery, even if we do not know the finest-grained details: animal behaviors derive from a delicate interplay between biological structure, inherited instinct, acquired learning, and environmental input. The behavior is automatic rather than chosen, but that is not to say that it is deterministic or inevitably any given response, since so many of the factors, and certainly their interactions, will be unpredictable in their results.

Notice however that there is no serious question about the appropriateness of automatic animal behaviors. The animal behaves as it does, it cannot help it, and it makes no sense to ask whether what it did was ‘right’. We might judge an animal’s action against the statistically normal activity of its species in order to say that it is doing better or worse from a natural selection point of view, or we could imagine a version of the same animal with better instincts, but it is not as if the malfunctioning or inferior animal should have known better or should have thought more carefully. We do not hold its automatic behaviors against the animal. Yet we do make such judgments about knowledge and rationality – which goes to show that none of this automatic behavior concerns epistemology yet. To make knowledge possible, another level of complexity is required.

Representation-Governed Behavior

A great deal of the behavior of all animals, including of human beings, is governed automatically. But some animals have more flexible capacities than what purely automatic living things can exploit. Some animals possess minds that enable them actively to seek equilibrium with the environment in a way that is different from both rocks and ants. Having a mind entails the capacity to represent other things, and this implies a rich repertoire of interacting, interrelated representations.

Mental representations are a kind of mental intermediary ‘between’ a living thing and the world to which it responds (‘between’ must be in quotation marks because, of course, the living thing carries this intermediary within itself). One way to put it is that cognitive beings behave on the basis of mental ‘descriptions’ of the world that say something to the cognitive agent about how the world is. Descriptions can be language-like, as they may be for human beings; or they can be given in terms of some other medium that describes, such as in images. A useful metaphor here is of a cognitive agent’s representations as comprising a map. We can imagine that the cognitive agent carries around a small book of such maps, and that it is the maps that she is responding to mentally. These maps describe the environment using resources that are quite different from the environment itself. Nor does the map have to be entirely accurate to enable successful navigation. In many cases complete fidelity would be cumbersome and distracting. Rather, a useful map needs to encode a description of the environment that suits the immediate needs and purposes of the map user. Thus representations might be something very simple like the orientation of a line on a two-dimensional surface, or might be very complex like the conceptual description of a social situation. One important branch of psychology, cognitive psychology, investigates the representations had by human beings, and by some non-human animals.

Instead of being wholly governed by instinct and conditioning, the descriptions cognitive beings carry around can interact in complex ways (eg, in thinking). A single representation might be triggered by very diverse stimuli, or trigger different responses, or diverse representations might well all trigger the same response. So the representations can interact independently of the world to some degree, in the sense that they are not locked into single pairs of stimulus/response relations. So descriptions are immensely useful in that, if the interaction of these intermediaries is governed by rules different from the rules governing what is happening in the environment, the agent has a rich set of extra resources to exploit which afford a flexibility in behavior that no merely mechanically active agent has. Therefore the point of decoupling behavior from stimuli through representations looks to be to give active beings a chance to operate in an environment distinct from the physical environment. We cognitive beings ‘behave’ in a world that does not physically exist, the world of the descriptions, in order to consider and make plans about situations that do not now exist. Here the stakes are much lower and we can go back to earlier steps in our plans to try out different behaviors. That is what planning is.

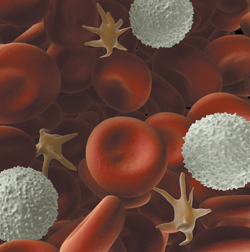

Neither right nor wrong: white blood cells zealously guarding your veins

The most important consequence for epistemology of under-standing cognitive beings in terms of representations, is that the way they represent may at times be inadequate for the purpose of staying in equilibrium with the environment, or just plain wrong. With merely automatic behaviors, it did not make sense to ask whether an action is right or wrong. If a white blood cell attacks healthy tissue, we would not say that the cell “thought the tissue was an antigen, but was wrong.” Well, we might say this, but we would be talking wholly metaphorically. That is because cells do not think anything, they just automatically behave. But in the case of a human being who mistakenly grabs a piece of plastic fruit from a bowl when she is hungry, it is not in a metaphorical but in a literal sense that we say “she thought it was a real piece of fruit, but was wrong.” The way we can make sense of the difference is by claiming that human beings, but not cells, represent the world. In this case the human being is incorrectly representing the objects before her as real fruit. The description that is governing her behavior is wrong – although it will be quickly corrected.

Epistemology As About Correctness

We may now summarize the big picture of epistemology as follows. Non-living things can be connected and arranged into living things in distinctive ways, to achieve persistence and integrity in the environment in a manner that cannot be achieved by non-living things individually – when these non-living parts comprise an active organism. When living things reach a certain level of complexity, one way they may increase in survival fitness is for their behaviors to be decoupled from automatic responses to the environment. The way to break this direct connection is for there to be an intermediary between the stimulus and the response, so that the organism’s response is to the intermediary rather than to the stimulus. We can then legitimately ask whether the intermediary is an adequate representation of the environment. It may not be, and the downside, when the representations are flawed, may be considerable. But the upside of having correct representations is enormous. By and large, evolution has made sure that in normal cases the representational intermediaries are not too far out of step with what is required for a cognitive animal to be successful in their particular environment.

We are already well toward our goal of locating epistemology in a broader understanding of the function of mind. Earlier, we identified good reasons as ones governed by rules that keep beliefs grounded in stable sources of evidence about the world, such as perception and (at least in some cases) memories and testimony. We can now say that the rules of good reasoning range over representations. In fact, the capacity for representations is essential for there to be epistemological rules at all.

For some epistemologists, investigating the unconscious (automatic) rules of thought is the most important part of epistemology. But a final step to epistemology in the broadest sense has to do with consciousness. When representations are available in the form of language, we can even string them together into articulate descriptions regarding everything from the most mundane aspects of life to the most intricate scientific theories. When we form such representations with the goal of avoiding error, they comprise our beliefs. Moreover, when representations turn into beliefs, we can investigate and question them explicitly by asking what makes some beliefs good and others bad. Relatedly, we can also ask, how can a self-conscious agent maximize her good beliefs? Are there habits, procedures, or mental policies that help us generate beliefs that are more adequate to or more accurately representative of the world? These are the sorts of questions traditionally asked by epistemologists.

The freedom, flexibility and adaptive advantage of the capacity for belief also comes with costs. Uncountably many things can influence the way we represent the world, and many of them can draw our beliefs away from a correct description of the world. Epistemology, then, is about closing the gap between the beliefs we have and the best beliefs we can obtain. It is the study of how and what it means to have representations that are well-enough matched up to situations that those beliefs will yield successful behaviors. The most successful beliefs, that is, the ones that show themselves to be such that they can perpetually keep us in organic equilibrium with the environment, are what we call ‘knowledge’. The beliefs that are more provisional, but which are related to the other beliefs in such a way as to give them considerable pedigree in keeping us in equilibrium, we may call ‘rational.’ Thus we have arrived back at epistemology, but by way of trying to understand natural sophisticated active living cognitive beings in the world.

© Dr Joseph L. Cruz 2013

Joe Cruz is a professor of philosophy and chair of the cognitive science program at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. He is the co-author, with John Pollock, of Contemporary Theories of Knowledge, 2nd Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999).

Knowlege and Reasons by Joe Cruz...

VIDEOS:

Richard Rorty on Pragmatism and Truth

Pragmatism and Truth podcast

American Philosopher playlist...

==

UPDATE, Sep 15: Good discussions, I've enjoyed my block-time with you.

Here's info about my upcoming summer course, hope to see you there:

New MALA Course, summer '24: "Americana..."

"Americana":

Streams of Experience in American Culture --

Exploring the American cultural experience and experiment, in light of classic American philosophy's traditional promotion of individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We'll identify and clarify "philosophical ideas at work in the task of understanding the fabric of American culture."

TEXTS:

- John McDermott, Streams of Experience: Reflections on the History and Philosophy of American Culture

- Carlin Romano, America the Philosophical

- Doug Anderson, Philosophy Americana: Making Philosophy at Home in American Culture

Hello everyone! You can pronounce my name as "Shy-anne"! It is unique spelling, but a name that's likely familiar to many of you. I am here because my dad's GI Bill pays for my education and I missed learning in an academic space! I would define knowledge as a collection of information that you have gathered or the collection or sum of all that you know. Another thing I would add about knowledge is that it is truth, things that cannot or should not be argued. One of the most important things that I know would be people's names, I know them by asking and remembering. Names are important, because it shows great effort in being intentional to remember them and show that someone matters. The most important thing I know is the Good News of Jesus! I know it from the Bible and am grateful to believe in someone like Jesus. I wouldn't say I'm necessarily skeptic about knowledge, but I can be. Looking forward to our block over this area of study.

ReplyDeleteHello Chianne,

DeleteI have only known you for a short while and I know if your fathers GI bill was not available you would find a way to be here. you have a true thirst for knowledge and understand the importance. we have worked on projects together and I have experienced your tenasity and attention to detail first hand. I must say, meeting a person your age with the kind of drive you possess is a rare treat and I consider myself lucky to know you.

Hello my name is Richard Fisher, I am a retired military veteran who through service to my country, was afforded the opportunity to attend college basically free. I like to consider myself a researcher of life. I enjoy traveling and experiencing other cultures. I personally feel you should never give up on your quest for knowledge, there is no such thing as enough knowledge. As for my definition of knowledge, I see knowledge as something you will never quite achieve. The more you learn the more you realize you do not know. No matter the subject you choose, there is always someone that knows just a little bit more, because no one knows everything.

ReplyDelete“No matter the subject you choose, there is always someone that knows just a little bit more, because no one knows everything.” — I love that you say that! Knowing this and believing this creates in us a hunger for knowledge and shows that as we each grow deeper in knowledge over a range of topics, we benefit and sharpen one another! Because we can’t know everything, we must depend on others’ research/life experience… It’s a beautiful thing! “The more you learn, the more you realize you do not know.” That is too true! I feel that as we’ve gone through our Foundations classes last semester.

DeleteThanks for your intros, Chianne and Richard. Looking forward to tonight.

ReplyDeleteHello to all. I'm here pursuing the MALA degree out of a pure love of learning acquired later in life when time has permitted such a luxury. I believe I have to say that to me, knowledge is what you think you know. Some things are concrete--your experience--yet it is different from anyone else's experience. Some knowledge seems concrete, yet I've seen so much of our knowledge change over the years and become clearer and so much more expansive that I hesitate to think of much as concrete. I say this because when I returned to complete my B.A. in 2020, nearly everything I learned had been discovered (or refined) since the last college class I had taken 35 years before. Therefore, I only really claim to know my own experience, and maybe the most important thing I know is myself.

ReplyDeleteSo said Socrates. "Know thyself." And for most of us, it takes at least 35 years to begin to really do that.

DeleteIn chapter 2 of our readings, Aristotle’s answer to increasing eudaemonia was intriguing to me, “‘develop the right kind of character,’ you need to feel the right kind of emotions at the right time and these will lead you to behave well…” (p. 12). My question in response to this is: is being a person of good character enough to ensure that you’ll be dealt a good hand?

ReplyDeleteMy spiritual and religious beliefs guide me to believing otherwise, but based on Aristotle and other philosophers… Having good character is the catalyst for good behavior/good outcomes. “Instead of looking to increase our pleasure in life, they think, we should try to become better people and do the right thing. That is what makes a life go well” (p. 13).

What about all of the things outside of your control? We cannot control the actions of others and trust that they would also act to the highest character morale.

That's where the stoics come in...

DeleteIt was both an encouragement and challenge to me reading in chapter 3 that Pyrrho believes “we can’t completely trust the senses. Sometimes they mislead us” (p.16) and “absolutely everything was simply a matter of opinion” (p.18). These two things then lead to him worrying less than the average person being that without things being absolutely true, there is nothing to fret about. I wish I could even for a little bit with this mindset, but I am very practical and depend heavily on my senses.

ReplyDeleteI can see how freeing it may be in his belief though. I could probably live more like him if I more frequently believed and lived by this: “Unhappiness arises from not getting what you want. But you can’t know that anything is better than anything else. So, he thought, to be happy you should free yourself from desires and not care about how things turn out” (p. 19).

Your comment made me want to go back and read this chapter, as it was not one of the four I chose. I can see how that mentality can be freeing, but I agree with you in that I am practical. I think it can also be damaging as a society to think that you can’t know with certainty that anything is better than anything else. If we all held this mentality as strictly as it appears Pyrrho did, would we ever want to seek growth or to better ourselves or the world around us? It is certainly easier and more peaceful to think as Pyrrho did, though, so I can see the appeal.

DeletePyrrho wouldn't have lasted a minute, with his "don't care" attitude, were it not for a substantial posse watching out for him and keeping him from harm's way. I think moderate skepticism (which all philosophers have) is good, extreme (like P's) bad.

DeleteI wouldn’t last with this mindset without my posse either. I imagine finding myself in a lot of trouble if I lived out a “don’t care” attitude. It does seem it would be easier and more peaceful as you say, Chelsea! However, I don’t see that philosophy as sustainable, even though I wish it would!

DeleteHello everyone! I currently work at MTSU as a Strategic Communications Coordinator for the Office of Undergraduate Admissions, and I am utilizing my free classes as an employee to complete my Masters in Liberal Arts. I am hoping to later go into a PhD program for Anthropology, either specifically in Biological Anthropology or Paleoarchaeology.

ReplyDeleteI found Hume's discussion of the Design Argument interesting. The Design Argument itself is understandable - it is hard to connect the world around us as a coincidence. If there was even a slight difference in the ratio of dark matter:normal matter, we might not exist (at least not in the sense of how we understand our existence now). However, as Hume points out: does this then mean that a creator was responsible? If so, how do we know which religion's god it was? I don't think we can know just through this argument alone. This does not necessarily mean that a creator of sorts did not create the world as we know it, it simply means we may not be able to tell which creator it was simply through the use of the Design Argument.

ReplyDeleteBear in mind that Hume wrote pre-Darwin, whose account of natural selection offers an alternative to deliberate design. It's a form of design that does not require a designer at every step of the evolutionary sequence, but that (as Darwin also acknowledged) does not preclude the possibility that the entire sequence may have been initially commenced by we know not what.

DeleteThe design argument is very intriguing to me and definitely requires much more thought out of me. In the past few years, I’ve begun to look at things like creation and design solely through the lens of my religious/beliefs. I acknowledge that this could be faulty, but that’s where I am! Reading these different philosophies is definitely stretching my thinking and challenging/sharpening things I believe are true.

DeleteDescartes' skepticism followed by the concept that God must exist because he can conceive the idea of God. This seemed a bit out of character of him given his prior skepticism. Can we truly prove the existence of a God because we have the idea of God - particularly when his idea of God derived from the information he received from his senses (which he previously doubted) through word of mouth or through written word? It seemed as though he did not want to acknowledge that perhaps one of his firmest beliefs would not be present if he had not gained the knowledge of it through his circumstances. Now, the argument he provided would be more sound (the idea that a good god would not deceive); however, this is also forgetting that other beings could in fact deceive.

ReplyDeleteI thought about this entry a lot and see this as a similar argument that most Christians use in defense when asked how they can prove God exists. The argument that God exists because just the concept of God means he exists. My question has always been how do we know our God is the right God? And I have always been told that's where faith comes in.

DeleteI find this very interesting. I keep looking at the time in History with all this and I feel maybe Descart didn’t want to raffle feathers. The only reason why I’m saying that is it doesn’t go with his previous believes. That’s just my take!

DeleteDescartes' idea that just because we can conceive of something must make it so was a surprising one for me, period. Following that line of thinking, there are really little green men on Mars, a pot of gold at the end of rainbows, and all sorts of monsters that we've seen in movies. Every individual who has ever lived may have had different ideas/concepts of something, but that didn't make them true empirically. I just can't reconcile that idea with such a 'thinker.'

DeleteWell, Descartes would say his strategy is a bit more sophisticated than just the bare assertion of something like Anselm's argument (that our concept of god necessitates god's real existence). He introduces the test of clarity and distinctness, and invokes god to guarantee the reliability of that test. But how does he vindicate his idea of a guarantor god? His clear and distinct idea thereof. Seems circular, right?

DeleteThis is a good question. I think the only answer is that everyone makes conclusions based on their own personal experiences. What if we actually are all speaking of the same force/intelligence? – That would be almost comedic to me, considering the dispute and chaos that wreaks in our disagreements as a society.

DeleteI have always enjoyed pondering wether or not Socrates as we know him was actually truly represented by Plato or sometime used as an alter ego to off set Platos teaching in a desired way. One if my favorite musings of Socrates is the story of the people in the cave watching shadows on the wall and this being their whole world. I feel this can be seen in several places in todays society. like what we discussed in class regarding the Disney movie "Wall-e". We as a society have become so wrapped up in our own lives that we sometimes fail to see what is truly goin on around us. The external stimuli or the one person how ventured outside the cave are shunned by the collective to the point that even those not involved not directly follow the masses instead of acquire their own information. This in my opinion is similar to the "5 monkey experiment". As time goes on the masses will forget why they don't like something or don't trust something, they will eventually stop even questioning the "why".

ReplyDeleteI can see where our society could become the movie Wall-e and I have hopes it doesn’t. I want to believe there is hope for the human race but the pandemic, showed me. Maybe not.

DeleteWall-e World is already evident in germ, in students who'd rather ride an electric skateboard that exercise their two good legs. Of course that could just be the crotchety opinion of an older person.

DeletePragmatism in my opinion can be a useful ideology when It comes to research. If I understand it correctly this encompasses alternative views and allows for different contextual view points in regards to a specific problem. In my research of human trafficking it is important to explore more viewpoints so as to not cover every supposed case with the same definition. For example not all human trafficking involves sex a lot which is called human trafficking is truly labor trafficking like we see in and around Nashville. So if you only viewed this as a sex crime you would miss a large portion of this deeper issue. I didn't even realize I was conduction my research through a pragmatic eye.

ReplyDeleteSpeaking as a pragmatist I of course want to say that flexibility and non-dogmatic openness to reconstructing problematic situations such as you describe is distinctively pragmatic... kind of like the anecdote of James's squirrel.

DeleteHello, my name is Kendra Gardner this is my second semester going towards my Master’s.. I hope I’m doing this right I’m a little special when comes to this. My undergrad background is in History and German. I had brain surgery 5 years ago last semester was my 5 year marker. It affected my right side and my ability to walk. I lost all my fine motor skills and the ability to speak. Words were/are hard to come out and I have to think really hard sometimes. Thus not speaking a lot. I have grown a lot from where I was 5 years ago.

ReplyDeleteYou are a remarkable person and an inspiration in your determination and accomplishments in the last 5 years!!

DeleteKaren's right. Hope to see you in class again!

DeleteSo proud to know you, Kendra!!!!

DeleteIs Aristotle’s doctrine of the Golden Mean relevant today?

ReplyDeleteIn my opinion, the answer is a resounding ‘Yes!’ As adults, I think those of us in this class have likely experienced enough of life to see that virtue typically does lie between two extremes. For most of my adult life I have followed the adage that seemed like sound reasoning to me, “all things in moderation.” It has seldom, if ever, let me down. And I would say it does help to develop virtues, in that individuals who are in the extreme one way or the other are seldom considered virtuous in that regard. To successfully live in society, which was another of Aristotle’s concerns, staying more ‘middle of the road’ seems to pay off for most people.

It's easier to see both sides from the middle, for sure. But Aristotle is not saying what I've heard people sometimes claim he said, that we should always reject sharp opinions when they conflict with an alternative that's false. The midpoint between a correct view and its extreme false alternative is also false.

DeleteIs ‘truth by authority’ still active?

ReplyDeleteBoy, is it—perhaps more so than ever. And, of course, ‘the Church’ is the ultimate authority which trumps virtually everything/everyone. The Church, and ‘they.’ “Well, ‘they’ said…” Having lived as one of the few people who has challenged various authorities, I can say we are not appreciated. Like the early philosophers, we threaten the status quo by our questioning authority. We threaten the power structure. We threaten people’s comfort level. We are seen as troublemakers and as somehow dangerous. Truth by authority is insidious and infuriating, but I don’t think it has ever been more entrenched than it is today, with more ‘authorities’ than ever before thanks to social media. Truth by authority is what is dangerous and may well lead to death by complaisance.

Long may we gadflies wave!

DeleteWhat fields other than philosophy are pragmatic?

ReplyDeleteJames describes how religion is truly Unpragmatic, and how science has moved toward pragmatism in some ways. I especially liked his suggestion that the definition of physics be, “the science of the ways of taking hold of bodies and pushing them.” That’s understandable—much more so than, “the science of masses, molecules, and ether!” I find that my field of anthropology is supremely pragmatic, always aware that new information is just around the corner, and evidence consistently stated as, “what we know at this time.” Rather than going into the details of the 4 subsections of the field (biological, linguistic, cultural, and archaeology), the definition of anthropology is simply, “the study of humanity,” (or what makes us human). As a cultural anthropologist, my favorite is, “the study of all the ways of being human.”

As a self proclaimed Cultural Anthropologist I could not agree with you more. I am always seeking more information in regards to my research projects and in my life in general. I enjoy learning how we have more in common with other culture than we realize. I also find it interesting to look at my research through other eyes to see how others could influence the way I see my projects.

DeleteEncouraging and celebrating varieties of ways of being human is what WJ's pragmatic pluralism (and "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings") is all about. Sadly we seem to live in a time when "my way or the highway" is more often touted.

DeleteWould you agree with James’ view that belief that God exists is a “useful belief to have?”

ReplyDeleteFor me, this is a tricky question. On one hand, I agree. If one believes that a God exists who has A) established rules of behavior; B) is judgmental; and C) will be handing out rewards or punishments at a future time dependent upon adherence to those rules, that can and does control behavior. Some are controlled by the belief much more so than others, and in general it would seem that those rules of behavior are positive personally and for living within society. But I also see that some of the beliefs about rules which were supposedly handed down have been extremely harmful to not only individuals, but entire classes of people, and in some cases an entire gender. And we are probably all aware of the enormous toll of religious wars. A pure belief in ‘God’ is likely positive—an appreciation of creation, etc.—but with the addition of ‘religion’ we have problems. And now I'm not sure how 'useful' a simple belief in God would be. Hmmmmm

I think this is a very interesting question, and I think that it can be useful. I think some people find comfort in the existence of God. However, I think from a pragmatic perspective, it is also interesting. A philosophy which relies on verifiable truths does not seem to necessarily seem to alone explain the phenomena that many believed linked to God. Perhaps, however, it is also important to understand that at the time this was written, much of the world around them was still being explored and explained through scientific means.

DeleteCAN be a useful belief, but as a methodically-neutral corridor monitor WJ must also admit that disbelieving in god works for some of us too:

ReplyDeletePragmatism "stands for no particular results. It has no dogmas, and no doctrines save its method. As the young Italian pragmatist Papini has well said, it lies in the midst of our theories, like a corridor in a hotel. Innumerable chambers open out of it. In one you may find a man writing an atheistic volume; in the next someone on his knees praying for faith and strength; in a third a chemist investigating a body's properties. In a fourth a system of idealistic metaphysics is being excogitated; in a fifth the impossibility of metaphysics is being shown. But they all own the corridor, and all must pass through it if they want a practicable way of getting into or out of their respective rooms." Pragmatism II

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5116/5116-h/5116-h.htm

Following up Richard's question about non-academic philosophers in America, some of the indexed figures mentioned in Carlin Romano's "America the Philosophical" include (besides playboy "philosopher" Hugh Hefner): Isa Asimov, W.H. Auden, Stewart Brand, Jimmy Carter, Robert Coles, Bob Dylan, Robert Frost, Henry James, MLK Jr., Bill McKibben, Bill Moyers,... And that's just a sample.

ReplyDeleteI've appended info about my upcoming summer MALA course "Americana: Streams of American Experience" at the top of the blogpost. Hope y'all can join us, in person or remotely on this site. Meanwhile, enjoy the rest of 6010!

DeletePragmatism seems to be a very literal, objective philosophy or framework of philosophy. It seems almost obvious that this should be the sole framework of what we consider as truth/knowledge. As we were talking about this in class, Professor Oliver said "if you want clarity in your philosophy, you have to know what knowing _____ means to you practically." So, my question to pose and for myself is what things do we wish to know practically or have truth on?

ReplyDeleteI found James' comment about theories as "instruments...in which we can rest" and that "Pragmatism unstiffens all our theories" (Lecture II) interesting. A question that came to me is this: in a time of so many theories, sound and unsound, what then becomes practical for us to believe? How do we as a society truly find the theories we can truly rely on (if only temporarily) in order to move forward in our pursuit of knowledge? I think to some extent, social media has been highly beneficial; we are able to access more knowledge and different perspectives than ever before. Yet, it is a double-edged sword: misinformation spreads as easily as truth.

ReplyDeleteI forgot to switch from Anonymous - this was written by me. :)

DeleteWho are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteI am resting my response heavily upon the premise of an acceptable literal interpretation of the question. That is to say, my name is James and I am enrolled in MALA to support my reintroduction back into society post military life. However, metaphysically, who am I? Why am I here? I only wish I had a shadow of a flicker of an idea.

How do you define knowledge?

Knowledge, I am sure to be a prickly thing. In my little life. I am only ever 100% sure I know something, until I realize that I was mistaken.

---

I received your very kind email a few weeks back - thankyou. I have some experience with classical Philosophy and will brush up before coming to class on Thursday. I feel I come to you as a child with rubber arm floaties in a turbulent sea, I won't drown immediately but should a wave or a shark come along, I will be in trouble! I have been looking forward to the philosophy module since I joined the course! See you Thursday!

Who are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteI am a member of the Baby Boomer generation and have a true love for learning new things and being surrounded by people who can further enhance my love of learning. This class has been so very wonderful, and my classmates have been responsible for a woman of my generation to feel as though I have made an excellent decision to further my education. I am a firm believer that you are never too old to learn new things.

How do you define knowledge?

My definition of knowledge is the ability to take what you have learned and know how to apply it to your everyday life. Without knowledge, persons who are existing in today's world are just going through the motions and not making a difference in their life and the lives of the persons you come into contact with on a daily basis. I have never taken any type of philosophy class before and am excited to be able and immerse myself into this subject. I will certainly put forth an honest effort to succeed.

Charlene, you and I are on the same wavelength. Although I was hesitant to continue in the master's program, I chose to do so to explore the heights of my abilities and share knowledge with those around me.

DeleteWho are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteI am a “folded” fitted sheet on the shelf in someone’s first apartment. Smooth and deceptively put-together at first glance on the linen shelf. Inside, I am a smidge disorganized and jumbled but resilient when stretched. Having been raised on Air Force bases most of my life, constantly moving and morphing to fit in, led me to a life where I want to stand up and make a difference… making myself seen.

Several people have asked me what I plan to do with my MALA degree. I respond to them, “learn everything I can along the way!” So, why am I here? I am here to fill my pockets with understanding, experiences, and knowledge.

How do you define knowledge?

Knowledge, to me, is the examination of information I currently possess and certain of and the gathering of additional information, some of which disproves or provides additional insight on the information I was certain of initially.

Michelle

A folded fitted sheet! I have never heard that one before! :)

DeleteWho are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteHello! My name is Johanna, and I am here because every decision I have made in my life previously (and arguably not 'decisions') led me to this place ;)

I am fulfilling a long held promise to myself to continue my formal education and learn as many things as I can, and spark some new joy. I'm enjoying the journey and excited to see what comes next.

How do you define knowledge?

I am very aware that the more you know, the more you realize there is to know (and, how much you don't know.)! Knowledge to me is the universe; ever-expanding, and unfolding. I can't even say I know myself fully, though I've spent 39 years hard at it.

Looking to class!

P.S. Philosophy noob here, excepting the standard teenage phase :)

Who are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteHello, my name is Seth Graves-Huffman, I had the lucky chance of having Dr. Oliver for class last semester! With that I am here a student of philosophy, but malleable, moreso a student of the humanities. I love seeing what rationalistic systems humans can concoct! But, in my lived life, I'll be turning 30 next month, I'm quite happy to be continuing in school, and I got about close to 10 pets at home!

How do you define knowledge?

Simply: how the people in a particular context choose to define it.

It is not that one system may be the supreme method of attaining knowledge, but that some systems may have more solid backing for its supposed place as a reverence of knowledge.

Thus for me, even if other systems might not have as strong backings to it I still really enjoy to see how different individuals and cultures construct their representations of the world that we live in.

Who are you? Why are you here?

ReplyDeleteHey hey my name is Justin Mitchel but everyone calls me Jay! I am fresh off of graduating from the fall of 2023 and I decided to why not and go ahead and get my masters while my thinking cap is still on. Why I am here is because it is always a plus to get a degree back to back like I am attempting to do, I can see it as me showing dedication to the main goal.

How do you define knowledge?

Knowledge is all around us and it is almost infinite with as many things someone can learn. It can be so eye opening learning about something that you thought you knew about and it adds on to your current knowledge and it make it even more interesting

For my discussion question I read over Aristotle's "True Happiness" and it was such a good chapter to read about understanding happiness. My big question would be how would Aristotle react to the current generation of happiness? With so much in the world revolving on technology it begs the question would their views change on happiness or stay the same. In my eyes I believe they would change drastically. With some of the main things like a sense of achievement it would be interesting to see how if in any way that their opinion would change.

ReplyDeleteJustin, you pose a great question. Aristotle would see our dependency on SM as a false sense of happiness. The definition of happiness has been redefined. Think about it: if the world went dark and our dependency on SM was deactivated, there would be many unhappy people. Aristotle wanted to explore "reality," and SM is far from reality in most accounts. "The best kind of life for a human being was the one that used the powers of reason". SM is void of reality and reason as we tend to take what we read as fact without research or critical thinking. His view or opinion of happiness would not change.

DeleteAfter reading chapter 19, "Rose-Tinted-Reality," I thought: In what ways does our perception influence the formation of reality?

ReplyDeleteOur perception is truly a filter for all information from the world. We use our previous life experiences, our senses and our thoughts to determine what WE consider reality. Because everyone has had different life experiences, process information differently through their senses and definitely have different thoughts - a group could perceive the "same reality" is a variety of ways... no two being the same.

I have often wondered how this "your red is not my red" style argument you are referring to relates to "universal truth."

DeleteThere must be only 1 reality, of which we all interpret, as you say, through our senses and experience. But, as you also say, both of those modes of interaction are not calibrated to be the same for everyone and every animal (bats included.)

So, either:

A) One perception is correct and interacts with reality in the manor in which it really is and all other interactions and interpretations are a modification of the reality

or

B) Every current interaction with reality are merely interpretations of it and no living thing has ever experienced the universal truth of reality.

What do you think?

Hmmm… I would probably lean toward B. Our understanding of reality is subjective, shaped by our unique experiences and interpretations.

DeleteMaybe this could be an example? In a courtroom setting, multiple witnesses can offer differing testimonies of the same event due to their individual perspectives, memories, and biases. This shows how our interactions with reality are colored by our subjective viewpoints, making it difficult to establish a universal truth or objective reality.

Hi Everyone!

ReplyDeleteThe man with the golden thigh... who can speak to the water... who convinced a bear to hunt elsewhere... a son of God... who doesn't eat beans or meat... the Father of unifying Philosophy and Mathematics...

...

The man who did not invent Pythagoras theorem: Pythagoras!

But wait, there is a record of him eating meat... And

Rousseau wanted to return to nature; but lived in luxury, had affairs and abandoned his children

Kant preached human value but owned slaves

Schopenhauer talked of passion but was notoriously rude and had an awful temper

.

And the list goes on…

The first question:

When a Philosopher transparently does not practice what they preach, why should we accept their moral authority?

On the one hand, it is very hard to assign credibility to one who proclaims: “Do as I say, not as I do.” I find that to be an impassable hurdle and an instant dilution of their opinions. However, I see that an argument can also be made that “only Allah is perfect” and that these thinkers are projecting what they think to be right as an ideal for us to strive towards in the spirit of “Let he who is without Sin cast the first stone.” Nevertheless, I sense that some of these thinkers do not project this stance and rather present themselves as emblems of virtue whilst maintaining their behavior behind the scenes.

The second question:

What is a chair?

This one has been the bane of many a conversation, especially with my Army friends. Can you tell me what a chair is? Not what it is made of. Not what a chair does. Not what it looks like.

Without appealing to its function, construction or subjective value. What IS it?

I so wish every philosopher was asked that question over time and we could compare their results! It sounds like a very Socrates style question that Plato and Aristotle would get rather upset about! Pythagorus probably wouldn’t care because you can appeal to mathematics as the ultimate pure knowledge to help and Kant would probably stab me with the scissors from his desk and Pyrro would undoubtedly declare that he doesn’t know!

Hi James,

DeleteSo to respond to your first question, I like the notion of Allah in this, as much of philosophy's history relates with religious inclinations, and certainly with the spiritual regards extracted from Plato and Aristotle as well. In that, a higher being represents perfection, and for us today regarding morals, we still chase perfection.

Maybe most of these moral philosophies that thinkers formulate are near impossible, not only for them but for anyone. But, maybe such philosophies become mentally enshrined as representations of possibilities of what we could be. For example, Kant's regard of not lying to anyone for any reason at all clearly has moral value, but is rather extreme. Certainly most find it ridiculous to ascribe to such, but, at the same time it personally becomes mythically enshrined in our mental repository of noble values, that we wish to ascribe to life. These people write the philosophies we wish to live, and often show us how not to live them.

Do we know that a philosopher would believe themselves to have moral authority over others? I am a parent - I will say with confidence that we should not let children use passive screens for many hours a day because it has a negative impact over time on physical and mental health. However, I absolutely let my children use screens (sometimes for hours a day.) I know something to be true, but I don't practice it. Why? Because I am human - I am tired, weak and unable to hold 'long term' impact as a motivator at all times and I cannot do everything, all at once to overcome their individual desire to stare at the screen for hours. That said, I stand by the truth that they are bad. And my children are either unaware of this truth, or they are aware but don't believe it, or don't care. That does not mean that I feel I have a moral authority over them. Morality of course goes beyond thoughts on screen use - but in their essence of being, and their limited, growing understanding of the world, I would not say they are less or more moral than me.

Deletecan't appeal* (couldn't figure out who to edit the post)

ReplyDeleteYou are not alone I could not figure out the edit function either.

DeleteComments can't be edited, just deleted (and re-posted with corrections). But if you really want to edit yourself, we can make you an author on the blogsite.

DeleteThe article, "The Man Who Asked Questions" truly resonated with me. I feel as though there are times when I feel as though I ask too many questions about subjects that I certainly should know more about. I feel as though Socrates was just trying to secure more information about different topics but in a very peculiar manner. I question what his thoughts were because he did not write anything down. I think the reason that he did not write anything down is because he would not l as thought it was necessary. Socrates also was a believer that face-to-face conversation was much better. I also am a firm believer in that practice. The article mentions that the word philosopher is derived from the word meaning "love of wisdom." had great influence on many people including Plato. He was a very influential person and the manner that his death occurred was very unfortunate. I will also feel as though, just as Socrates, that you will never know the answer to a question unless you ask.

ReplyDeleteThe article, "We Know Nothing," by Pyrrho was very troubling to me. The opening statement that shares that no one knows anything and that is not certain, is to be doubted. The action of skepticism is an action that I occasionally struggle with. My question would be what happened in his life that would make him feel that way.

ReplyDeleteHis intelligence made him have the ability, like Socrates, to remember things without writing anything down. His life was filled with events that gave him a great deal of favorable events such as not having to pay any taxes, but his thought process did not change. His actions encouraged persons to ask awkward questions but to seriously and critically think of the answers that are given.

Since Pyrrho believed that human comprehension is naturally constrained and prone to error. Our mental capabilities, such as reasoning and judgment, may result in divergent interpretations despite encountering identical data. For example, regarding the afterlife: The absence of direct empirical proof or consensus regarding what occurs after death serves as a reminder of our cognitive limitations.

DeleteDo you believe everyone knows exactly what the afterlife holds? Is there one consensus or right answer?

Michelle, I do not believe that everyone knows what the afterlife will hold but as a God-fearing Christian, I can only hope that I will be able to experience it. There are so many people who feel as though they everything about anything, but I am certainly not one of those people. Thanks for your response.

DeleteSchopenhauer's conception of 'Will' does not merely means our own subjective will, but a universal objective will; the fact that things move, and plants grow. No matter who or where we are, even if the regards of this 'Will' greatly differ, we all still live and operate in a universe 'willing'. For Schopenhauer, this went as far as one being able to realize that we all live in a single energy force, and to hurt another is the same as a snake biting its own tail.

ReplyDeleteSo my QUESTION: Does Schopenhauer's 'Will' bridge the gap in misunderstanding between the non-religiously, or non-spiritually, inclined individuals and the lived subjectivity of those identifying as spiritual or religious? OR also, does the realization of a universal will, one that we all share in, create a solidarity and connection with each other, to a near spiritual regard?

Personally I find this type of thinking is very important for two particular dimensions: morally and historically. Morally it is certainly beautiful to see and to feel a connection into a network, non material, that is universal to all others that we socialize and interact with. And historically, this feels near synonymous with numerous human historical takes of such human experiential relations with life and each other.

For example, the Greeks spoke of a force known as logos, something that pervaded the air, with the sentiment that one then knew what they ought to do, what is right to do. Certainly such a lens by Schopenhauer helps as lens of subjective relation to past philosophies. Or even how to now relate and interact with such. For example, even with the emotion of love, when the combined ideal of Kant, that, we view reality through a tinted lens, with the all-pervading ‘Will’ of Schopenhauer, then people actually have the chance to paint love overtop the world, and to operate and live within a world as such. However, how long that lasts may be the next problem.

My thoughts on Schopenhauer's "Will": I think Schopenhauer's idea of the 'Will' could act as a shared foundation for comprehending various religious and spiritual viewpoints (even those less familiar in the US like Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc.). The concept of a universal will, present in all individuals and linking us on a fundamental level, could go beyond distinct religious teachings and could be viewed/used as a uniting force.

DeleteI am a caterpillar whose transformation is overdue in a sea of beautiful butterflies. I am the caterpillar focused on the transformation rather than enjoying the journey to the transformation. Integrating the theories of Aristotle and Socrates, I approach the question of "Who am I and why am I here?" through the lens of self-awareness, virtue, and the pursuit of knowledge. I am a mom and grandma who chose to continue her education long after the average individual. I lost valuable time in the continuous quest for “something” that never seemed to satisfy me and complete my transformation into the butterfly. I realized to fully evolve, I needed to look inside myself and find what was missing. Aristotle believed in the concept of self-realization through the pursuit of virtue and fulfillment of one's potential. According to Aristotle, understanding oneself and one's purpose in life involves the cultivation of virtues such as courage, wisdom, and justice. I am here to complete my transformation, calling on the courage to continue my education when I can’t remember where I put my keys, the wisdom to accept new ideas and implement justice and purpose in an unjust world.