— Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance by Anthony Gottlieb

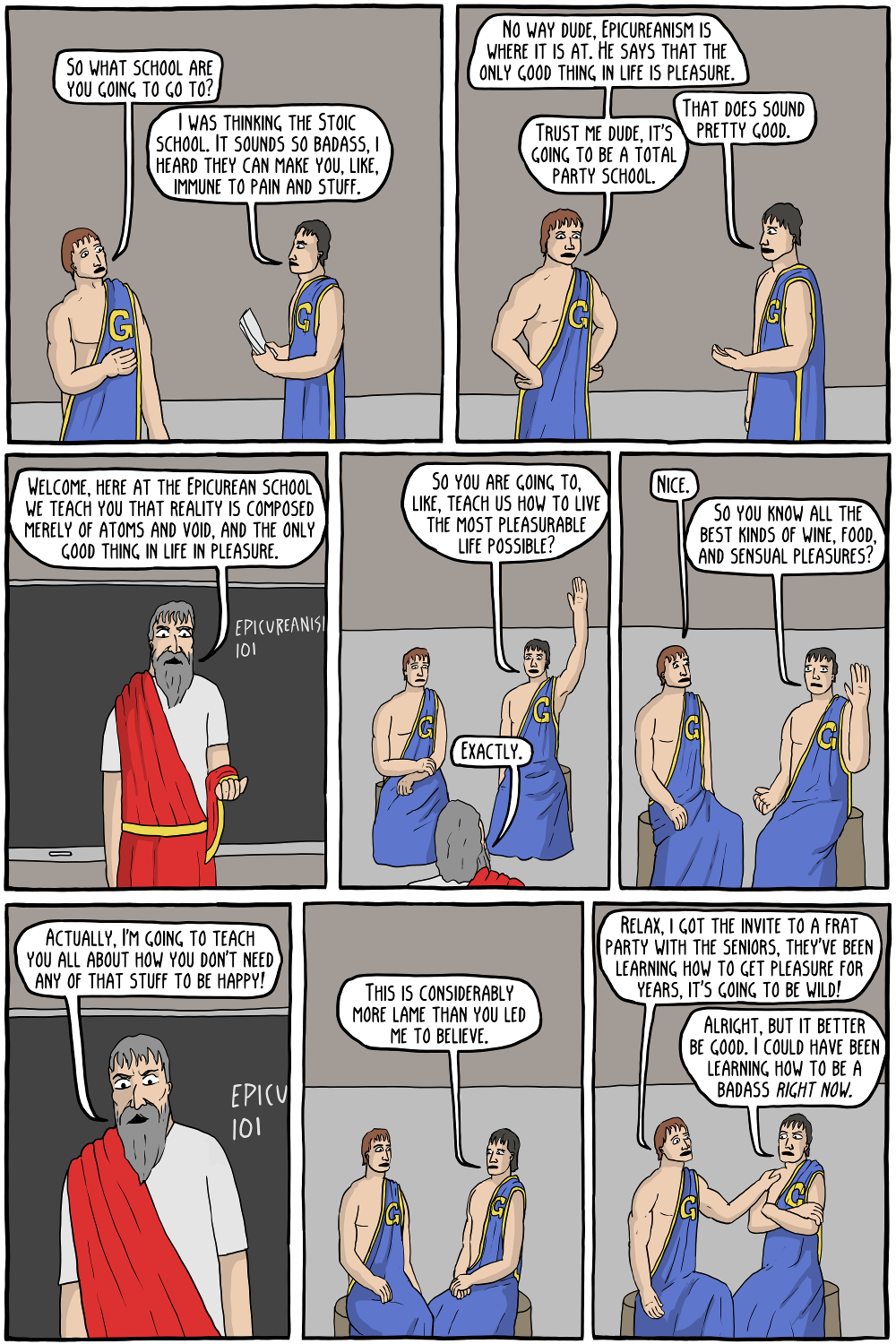

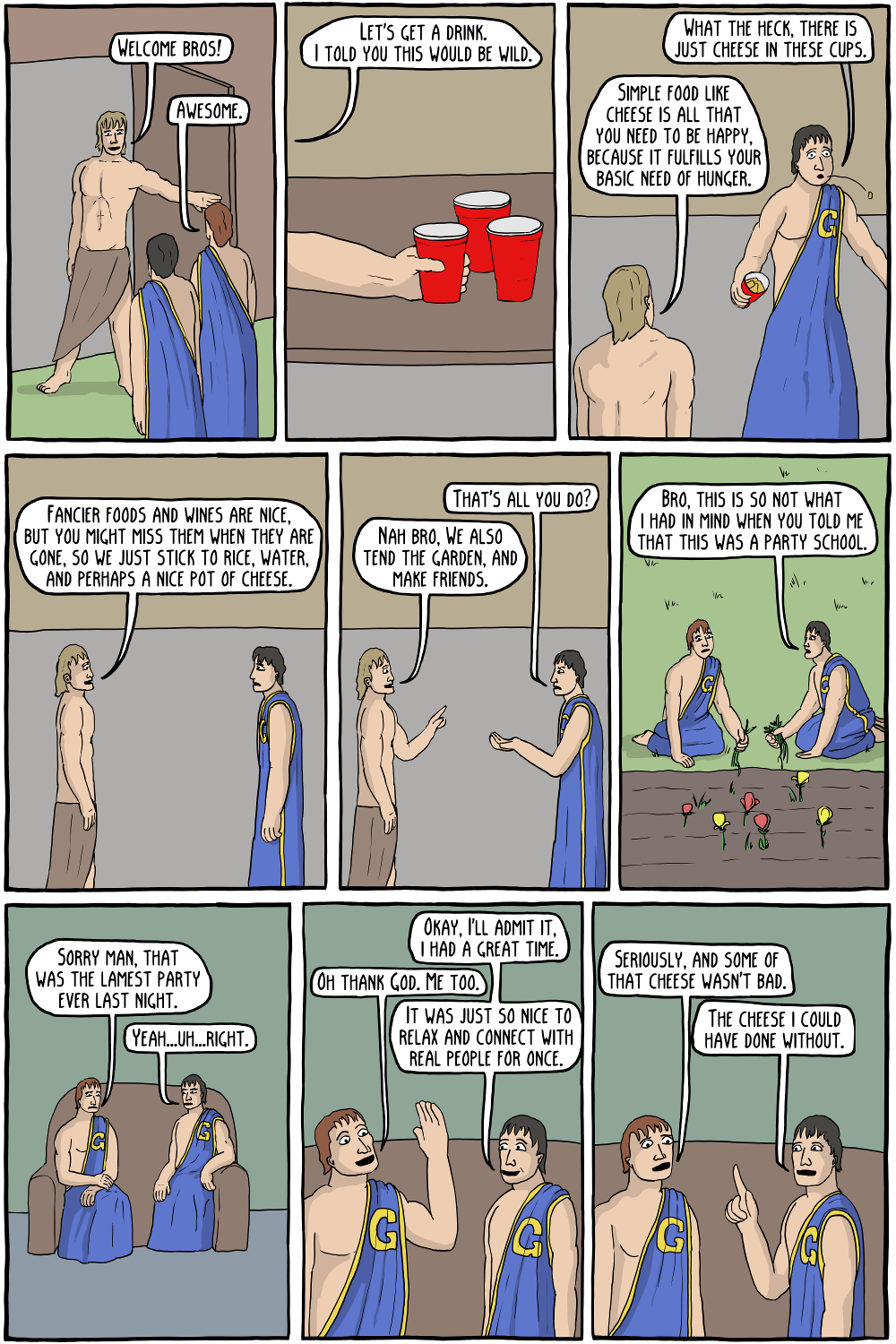

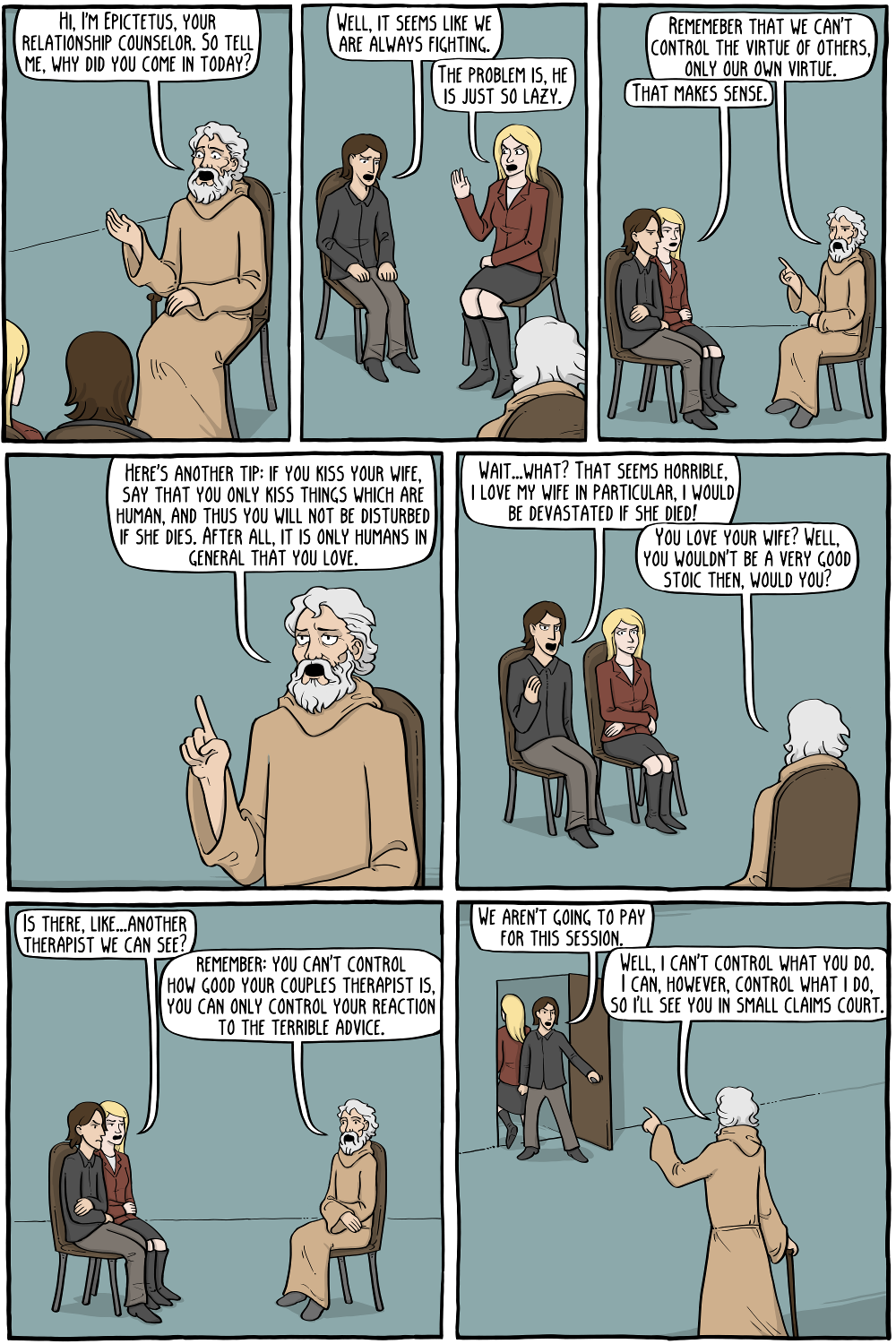

Graceful-life philosophies

I mentioned in my posted introduction to students that I consider myself a kind of epicurean, and invited them to tell us on Opening Day (for extra credit) what that means. This might help.

"Where the Hellenistic philosophies excelled was the production of what could be called secular religions. They were based on self-help–oriented doctrines often borrowed from the earlier philosophers but interpreted and presented in a way that made more direct sense to a lot of people. I'm calling them graceful-life philosophies to distinguish them from other philosophy. Their goals were practical happiness, and they were not merely theoretical about it: they provided community, mediations, and events. In this they were more like religions, but they did not identify themselves as religions and they had remarkably little use for God or gods.

The Hellenistic graceful-life philosophies had a lot in common. The experience of doubt in a heterogeneous, cosmopolitan world is a bit like being lost in a forest, unendingly beckoned by a thousand possible routes. At every juncture, with every step, one is confronted with alternative paths, so that the second-guessing becomes more infuriating even than the fact of being lost. After a direction is chosen, one is constantly met with another tree in one's path. What do you do if you come from a culture that had a powerful sense of home and local value, and now you are lost in something vast and sprawling, meaningless and strange? The stronger your belief in that half-remembered home, the more likely you are to panic, to grow claustrophobic among the trees and beneath their skyless canopy. Hellenistic men and women felt a desperate desire to get out of the seemingly endless, friendless woods.

The graceful-life philosophies of this period were able to achieve an amazing rescue mission for the human being lost in the woods and bone-tired of searching for home. They did this by noticing that we could stop being lost if we were to just stop trying to get out of the forest. Instead, we could pick some blueberries, sit beneath a tree, and start describing how the sun-dappled forest floor shimmers in the breeze. The initial horror of being lost utterly disappears when you come to believe fully that there is no town out there, beyond the forest, to which you are headed. If there is no release, no going home, then this must be home, this shimmering instant replete with blueberries. Hang a sign that says HOME on a tree and you're done; just try to have a good time. Thus the cosmopolitan doubter looks back on earlier generations with bemused sympathy—they were mistaken—and looks upon believing contemporaries with real pity, as creatures scurrying through the forest, idiotically searching for a way out of the human condition. After all, it isn't so bad if you just settle in and accept a few difficult ideas from the get-go."

— Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson by Jennifer Hecht

Thomas Jefferson: "I too am an Epicurean..."

And see The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt...

And Stoic Pragmatism by John Lachs...

And Epicureanism: A Very Short Introduction by Catherine Wilson

From old posts on Epicureans and Stoics--

But... are Epicureans good citizens? Have they retreated too deeply into their Garden to engage responsibly in the affairs of the polis? That's one of the questions we first raised when we last took up this topic in this course. It's still open. We may be stardust, and golden, and billion year old carbon (etc.), but aren't we also every bit as much products and stewards of our own time and place? Can we be Epicurean communards and still discharge the duties of properly concerned citizens?

...

LISTEN. It's on to Catherine Wilson's Epicureanism: A Very Short Introduction in Happiness today.

We're catching up, since Tuesday's class was pre-empted by the panel discussion on Suffrage and the Constitution. The Epicureans famously retreated to their Garden commune, in pursuit of life's simpler and less mediated pleasures. Would they have been engaged at all in the sort of civic activism that brought women the vote in 1920, or that is attempting to bring young people out to vote in 2020, or that tomorrow will bring citizens (the younger the better) out to demand action on the climate crisis? Would they have acknowledged any "urgent need of acting now," if that perturbed their garden delights? Where can we find the right balance between personal gratification and public commitment?

Those are some of our questions today. Others include

- Is it in fact foolish to fear "complete and personal annihilation"? -“To fear death, then, is foolish, since death is the final and complete annihilation of personal identity, the ultimate release from anxiety and pain.” ― Titus Lucretius Carus, On the Nature of Things... Gutenberg etext

- Do you think Epicurus was on the right track in thinking of atomic "swerve" as a "basis for free will"? 11 If they swerve randomly and unpredictably, how does that refute or challenge determinism? Or is his point that we can try to emulate their example and be random and unpredictable ourselves? Is random unpredictability really another name for freedom? (Remind me to tell my undergrad pub story...)

- Does Epicurus's analogy of atoms to "dust motes dancing in a sunbeam" remind you, as it does me, of Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot ("a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam" 12)? Do you see any parallels between Sagan's cosmic philosophy and Epicureanism? What about the "multiplicity of worlds" hypothesis vs. the view of Christian salvation as limited to "one small corner of the many world universe" etc. 16

- Do you think it will ever be possible to discover how and why the structure and activity of atoms in the brain and nervous system give rise to consciousness and the subjective feeling of selfhood?

- Do you agree that generation and dying are symmetrical processes? 51 In other words, do each of us owe the world a death? Do you find beauty and consolation in that perspective? Is death a peaceful sleep and a dispersal of spirit and soul atoms?