(Successor site to CoPhilosophy, 2011-2020) A collaborative search for wisdom, at Middle Tennessee State University and beyond... "The pluralistic form takes for me a stronger hold on reality than any other philosophy I know of, being essentially a social philosophy, a philosophy of 'co'"-William James

Friday, February 9, 2024

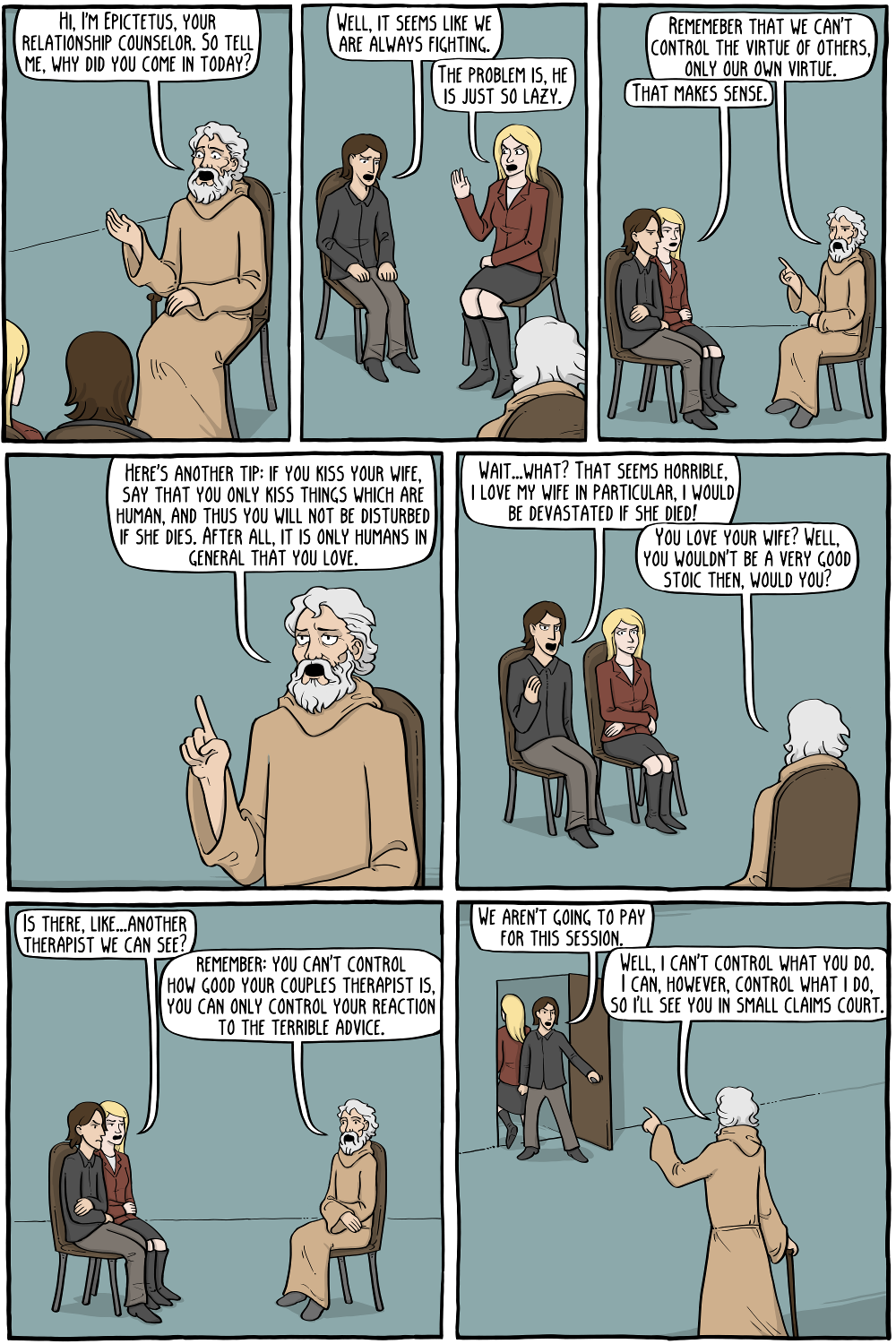

From Plato to Plotinus to Augustine to Christianity: “we are not very real at all”

"The most influential philosopher of the third century… is Plotinus (AD c. 205–270), a pagan teacher who studied in Alexandria and taught in Rome. His philosophy is otherworldly, deeply religious and entirely unmoved by scientific curiosity. Typically for his times, he tried to combine the ideas of many earlier thinkers while revering Plato above all. The mystically inclined thought of Plotinus inaugurated the final phase of Greek philosophy as it tottered over the brink of reason into occultism and religion. It was perfect for St Augustine (AD 354–430), who sometimes claimed that it contained everything that was important in Christianity except for the figure of Christ himself. It would be truer to say that Christian theology came to adopt many of Plotinus' ideas, partly thanks to the efforts of St Augustine.

Plotinus 'seemed ashamed of being in the body', said his pupil and biographer, Porphyry (AD c. 232–305). Plotinus thought of earthly life as a second-rate sort of existence, like that of the manacled prisoners in Plato's gloomy Cave. Inspired by Plato's talk of immaterial souls and of the ideal Forms which earthly things dimly reflect, he urged his pupils to focus on a higher spiritual realm. What he tried harder than any earlier Platonist to achieve was a grasp of the relation between the lower and higher orders of reality. Plato himself did little more than gesture towards a higher world, but Plotinus tried to draw a map that would show how and where the two realms were connected. The resulting theory, with its rhapsodic descriptions of obscure hierarchies, was spasmodically revived later on in European thought. Historians since the nineteenth century have generally called it 'Neoplatonism' to mark the fact that it goes beyond anything found in Plato.

Plotinus knew that he was trying to describe the indescribable. The goal of his philosophy was union with a God-like One, which he claimed to have experienced himself now and then. But although he could report such fleeting experiences of union, their very nature meant that he could not say much about them. He held that the One was beyond rational comprehension. It was so far above everything else that no ordinary concepts applied to it. In a sense, he admitted, it was misleading to refer to it as the 'One', because this invited the unanswerable question 'one what?' The One (or whatever) could not even be called a being, because it was 'beyond being', to use a phrase of Plato. Plotinus wrote that 'nothing can be affirmed of it—not existence, not essence, not life—since it is That which transcends all these'.

The One transcends everything else because it is the source of everything else. One of Plotinus' favourite images for evoking the indescribable way in which everything comes from the One is 'emanation'. Reality streams out of the One like light emanating from the sun. But this analogy is imperfect because it does not capture Plotinus' idea of a hierarchy of realities. Perhaps a more useful image is that of a cascading fountain in which everything flows from a pinnacle, the One, down to successive tiers below it. This flow from the One must not be thought of as a physical process, though. Indeed it is not really a process at all, because it is timeless. What Plotinus is trying to express is a truth about what lies behind nature as a whole; he is not just describing a particular natural phenomenon that can be explained in terms of cause and effect.

There are three main tiers to Plotinus' metaphorical fountain, each one in some sense 'overflowing' to produce what is below it. Below the spout-like One comes the level of Intellect, and below that comes the level of Soul. At the level of Intellect we find Plato's ideal Forms, which are also regarded as living intelligences of some sort. Intellect is an overflowing of the One, and Soul is an overflowing of Intellect. Soul can itself be divided into several subsidiary tiers, the lowest of which creates or overflows into the visible universe. Matter on earth is the lowest of the low. It is furthest from the One, which Plotinus also calls the Good, and this means that it is evil. Evil is a purely negative concept for Plotinus, connoting the furthest possible distance from the One or Good.

There are many degrees of reality for Plotinus, just as there are many degrees of goodness. Some things are more real than others, and the closer they are to the One, the more real they are. By this curious expression he does not just mean, for example, that horses are 'more real' than unicorns because horses exist and unicorns do not. What he means is that there are many gradations of reality even among existing things. Even if unicorns actually existed, he would still put them low down on his ladder of reality because they would still be nothing more than physical things—and Plotinus did not think much of those. This idea is a sort of perfectionism carried to extremes. Nothing can be regarded as fully real unless it is in every sense complete and perfect, which no physical thing is. For Plotinus, only the One that is absolutely complete. It is 'supremely adequate, autonomous, all-transcending, most utterly without need.' so only the One is absolutely real. Intellect is less real than the One, Soul is less real again, and we are not very real at all…"

— Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance by Anthony Gottlieb

https://a.co/3OEvDC5

Wednesday, February 7, 2024

If you have a powerpoint (etc.) for your presentation...

Here's the class policy (as posted in the sidebar) on slideshows:

If you have a powerpoint...

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

Walt Whitman, Epicurean

―Leaves of Grass

— Walt Whitman (1819 - 1892)

Questions FEB 8

Augustine, Boethius, Anselm, Aquinas-LHP 6-8. FL 9-10, HWT 9-10

LHP

- [Add your own DQs]

- Would the existence of evil equivalent to good, without guarantees of tthe inevitable triiumph of the latter, solve the problem of suffering?

- Why do you think Boethius didn't write "The Consolation of Christianity"?

- Do you think you have a clear idea of what it would mean for there to be an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good supernatural being?

- Do you think knowledge is really a form of remembering or recollection? Have we just forgotten what we knew?

- Is there a difference between an uncaused cause (or unmoved mover) and a god?

- Which is the more plausible explanation of the extent of gratuitous suffering in the world, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?

- Are supernatural stories of faith, redemption, and salvation more comforting to you than the power of reason and evidence? Why or why not?

- What do you think of the Manichean idea that an "evil God created the earth and emtombed our souls in the prisons of our bodies"? (Dream of Reason 392)

- Do you agree with Augustine about "the main message of Christianity...that man needs a great deal of help"? (DR 395). If so, must "help" take the form of supernatural salvation? If not, what do you think the message is? What kind of help do we need?

- What do you think of Boethius' proposed solution to the puzzle of free will, that from a divine point of view there's no difference between past, present, and future? 402

- Did Russell "demolish" Anselm's ontological argument? (See below)

- COMMENT: “The world is so exquisite with so much love and moral depth, that there is no reason to deceive ourselves with pretty stories for which there's little good evidence. Far better it seems to me, in our vulnerability, is to look death in the eye and to be grateful every day for the brief but magnificent opportunity that life provides.” Carl Sagan

- COMMENT: “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light‐years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. So are our emotions in the presence of great art or music or literature, or acts of exemplary selfless courage such as those of Mohandas Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.” Carl Sagan

- If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?

- Can the definition of a word prove anything about the world?

- Is theoretical simplicity always better, even if the universe is complex?

- Does the possibility of other worlds somehow diminish humanity?

- How does the definition of God as omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good make it harder to account for evil and suffering in the world? Would it be better to believe in a lesser god, or no god at all?

- Can you explain the concept of Original Sin? Do you think you understand it?

- Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

- Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you? Does it make sense, in the light of whatever else you believe? Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty?

- Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

- What kinds of present-day McCarthyism can you see? Is socialism the new communism? How are alternate political philosophies discouraged in America, and where would you place yourself on the spectrum?

- Andersen notes that since WWII "mainline" Christian denominations were peaking (and, as evidence shows, are now declining). What do you think about this when you consider the visible political power of other evangelical denominations? Are you a part of a mainline traditon? If so, how would you explain this shift?

Socratic irony

EUTHYPHRO: The best of Euthyphro, and that which distinguishes him, Socrates, from other men, is his exact knowledge of all such matters [as the true meaning of piety]. What should I be good for without it?

SOCRATES: Rare friend! I think that I cannot do better than be your disciple.

https://substack.com/@figsinwinter/note/c-48914388?r=35ogp&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action

Saturday, February 3, 2024

Reports begin Thursday

If you've not yet done so, please scroll down to Midterm Report Presentations and indicate your report topic/date preference.

Hope you all feel at home in the library now. Feel free to be creative with your reports, and integrate elements from the Maker Space (video, podcasts, 3D doo-dads, ...) if appropriate. Work with the Writing Center and our philosophy tutor, if that seems helpful. Just remember what Arthur said, having fun isn't hard...

Questions Feb 6

Epicureans and Stoics-LHP 4-5. Weiner 6, 12. Rec: FL 7-8. HWT 6-8 ... Don't forget to finish with Pyrrho first-see Questions Feb 1

2. How is the modern meaning of "epicurean" different from Epicurus's? Do you consider yourself epicurean in either sense of the term?

3. What famous 20th century philosopher echoed Epicurus's attitude towards death? Do you agree with him?

4. How did Epicurus respond to the idea of divine punishment in the afterlife? Is the hypothesis of a punitive and torturous afterlife something you take seriously, as a real possibility? Why or why not?

5. What was the Stoics' basic idea, and what was their aim? Are you generally stoical in life?

6. Why did Cicero think we shouldn't worry about dying? Is his approach less or more worrisome than the Epicureans'?

7. Why didn't Seneca consider life too short? Do you think you make efficient use of your time? How do you think you could do better?

- What was Kepos? What did Voltaire say we should cultivate? What do you think that means, philosophically?

- What inscription greeted visitors to Epicurus's compound? And Plato's Academy? Which would you personally find more inviting?

- Whose side in School of Athens was Epicurus on, and why? Do you agree?

- What is tetrapharmakos, and how might it help you distinguish Epicurus from Epictetus?

- Every life is what, according to Epicurus? Do you agree that this is grounds for celebration?

- Which American founding father declared "I too am an Epicurean"?

- What does Eric think happens if you follow the "good enough" creed?

- A common Stoic exhortation is... ? What is its core teaching? Do you think this is too passive?

- What did Diogenes learn from philosophy?

- What does it mean to say Stoics are not Spock?

- What did Epictetus have in common with Socrates?

- What is premeditatio malorum? Do you agree with Eric's daughter's assessment of it? Or with his, of her?

- What's "the View from Above"? Does it help you put events in your life in a better perspective?

- Have you experienced the death of someone close to you? How did you handle it?

- Do you care about the lives of those who will survive you, after you've died? Is their continued existence an alternate (and possibly better) way of thinking about the concept of an "afterlife"?

- Do you consider Epicurus's disbelief in immortal souls a solution to the problem of dying, or an evasion of it? Do you find the thought of ultimate mortality consoling or mortifying?

- How do you know, or decide, which things you can change and which you can't?

- Were the Stoics right to say we can always control our attitude towards events, even if we can't control events themselves?

- Is it easier for you not to get "worked up" about small things you can't change (like the weather, or bad drivers) or large things (like presidential malfeasance and terrorist atrocites)? Should you be equally calm in the face of both?

- Is it possible to live like a Stoic without becoming cold, heartless, and inhumane?

- What do you think of when you hear the word "therapy"? Do you think philosophers can be good therapists?

- Do you think "the greatest happiness of the greatest number" is an appropriate goal in life? Can it be effectively pursued by those who shun "any direct involvement in public life"?

- If the motion of atoms explains everything, can we be free?

- Is it true that your private thoughts can never be "enslaved"?

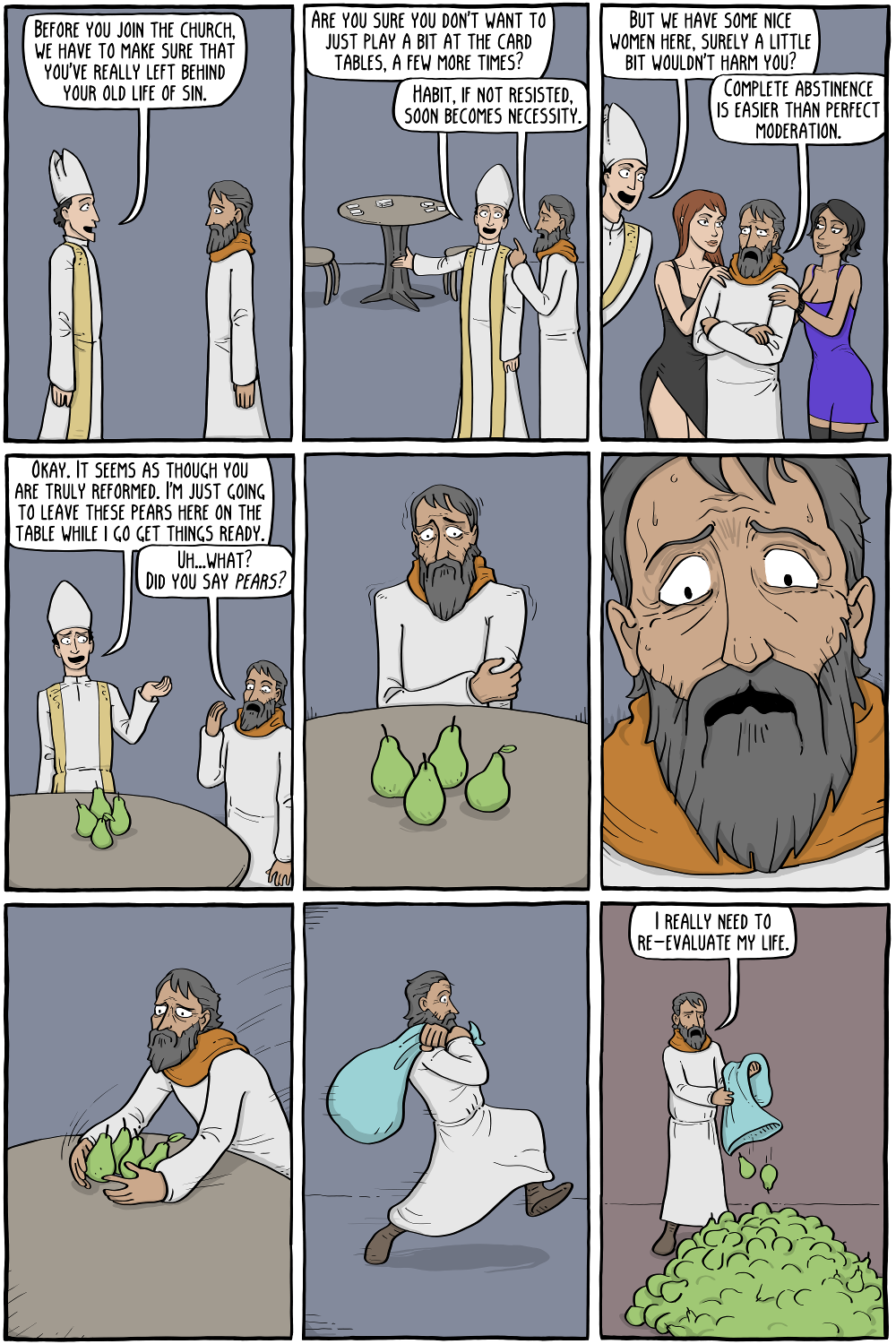

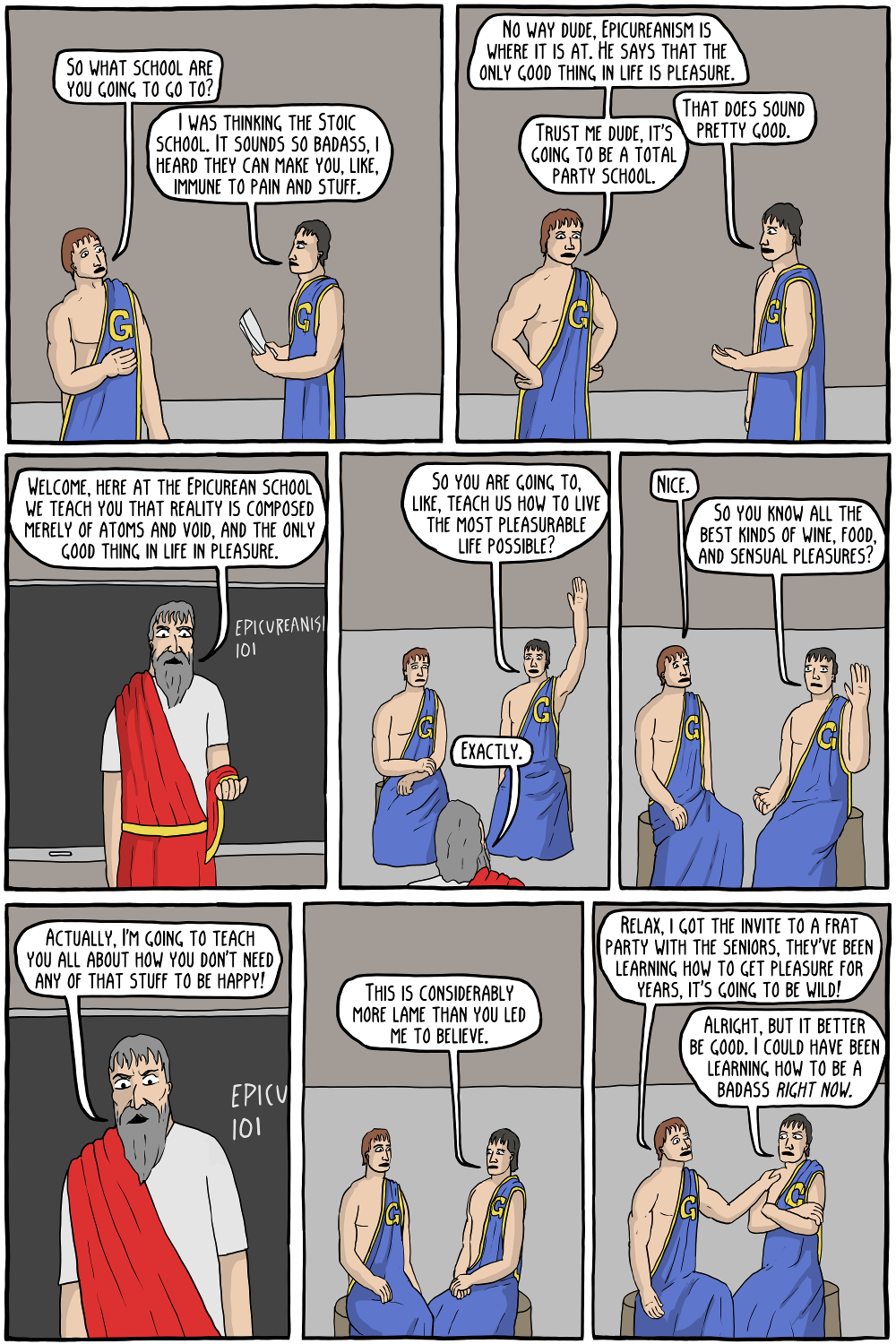

Epicureanism: The Original Party School

Permanent Link to this Comic: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/133

==

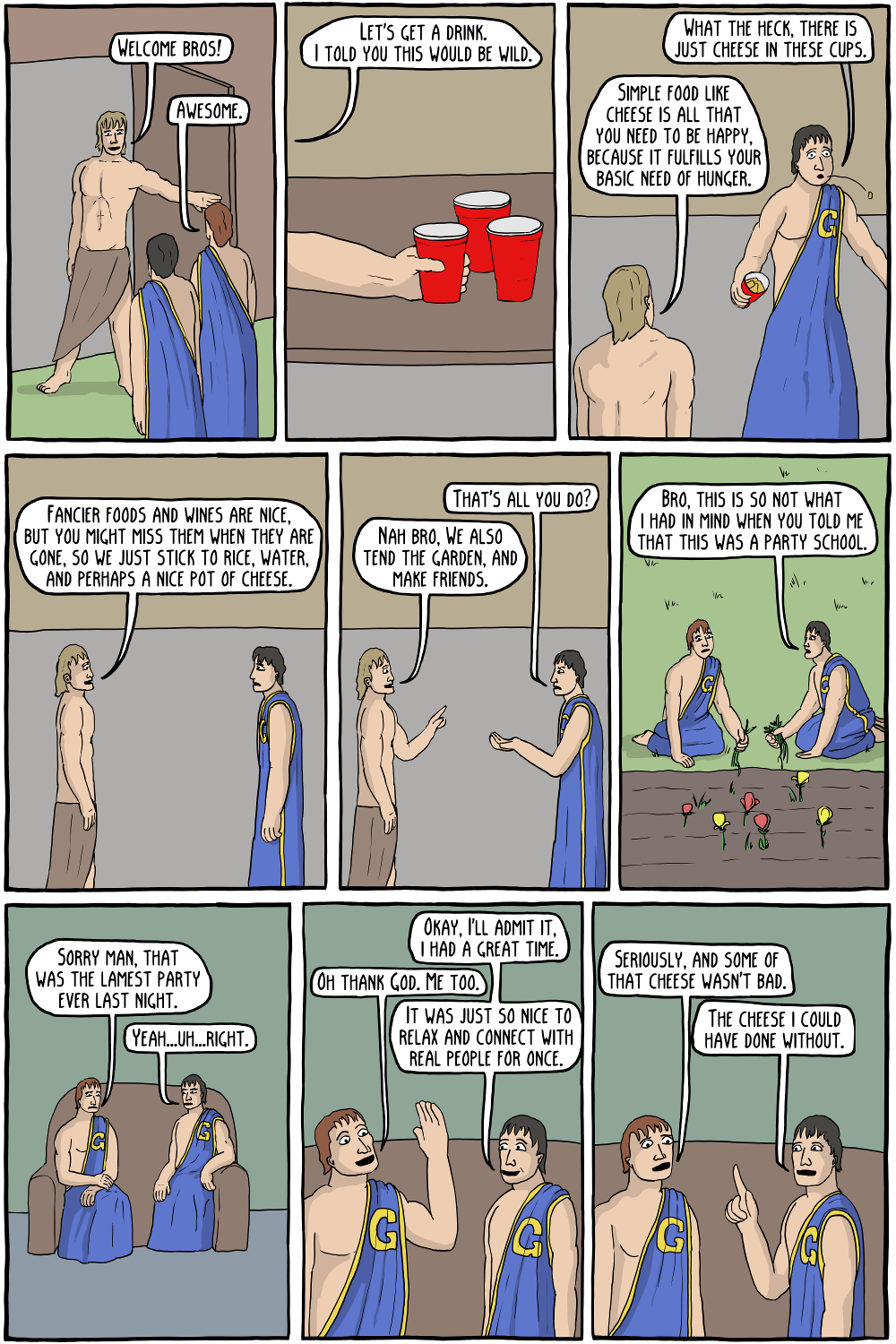

Philosophers in this comic: Epictetus. In The Enchiridion Epictetus gives the advice that in order to avoid suffering, we should not become too attached to particular things, so that when they inevitably end we are not caused undue harm. He starts with the fairly straightforward example of a cup that we like breaking:

With regard to whatever objects give you delight, are useful, or are deeply loved, remember to tell yourself of what general nature they are, beginning from the most insignificant things. If, for example, you are fond of a specific ceramic cup, remind yourself that it is only ceramic cups in general of which you are fond. Then, if it breaks, you will not be disturbed.

He then proceeds immediately to what seems a quite more drastic example:

If you kiss your child, or your wife, say that you only kiss things which are human, and thus you will not be disturbed if either of them dies.

Some may find that living in such a way is strange, to say the least.

Permanent Link to this Comic: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/264

==

Stoicism Man...The Next Great Stoic competition... Stoic apathy

Tetrapharmakos

The etymology of “tetrapharmakos” is quite simple: “tetra” means “four” and “pharmakos” means “remedy” or “medicine.” They are both Greek words.

Originally, the term refers to a compound of four actual drugs: wax, tallow, pitch, and resin. Later, it’s used metaphorically by Philodemus, one of Epicurus’ disciples, to refer to the core principles of happiness in Epicureanism, since both of them function as a “cure” and are four in number.

Philodemus put together the tetrapharmakos from fragments of his master’s teachings, and summarized them into four points:

- Don’t fear God.

- Don’t worry about death.

- What is good is easy to get.

- What is terrible is easy to endure.

Midterm Report Presentations

Declare your date/topic preferences. If your first choice has already been taken in your section, or if there are already two reports scheduled in your section for the date you indicated, please choose again.

Midterm Report Presentations (each worth up to 25 points... UPDATE Jan 17: Our weather postponements have pushed the dates all back a week, at this point. We were going to start presentations on Feb. 1, we'll instead plan to start them on Feb. 8. Early volunteers encouraged.)

Indicate your topic & date preference in the comments space below (include your section #; don't request a topic someone else in your section as already selected, or a date that's been selected twice).

In your presentation, summarize the information about your topic in our text(s), then tell us something interesting you've discovered about it in your research. Give us a discussion question or two, and lead the discussion.

FL, HWT, and the other non-required texts are available for 3-day checkout at the library reserve desk. Check the philosophy stacks for relevant books. For online research a good place to start is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

You don't have to post anything to accompany your midterm presentation (though you may); you will need to do a blog post accompanying the final presentation, more on that later. Plan to speak for a minimum of 10 minutes (plus discussion); maximum two (occasionally three, only if necessary) report presentations per class... so again, please don't request a date in your section that's already been selected twice.

FEB

- Augustine (see LHP)

- Boethius (see LHP)

- Something discussed in FL 9-10 (The Great Awakening, Cane Ridge, Joseph Smith,...) or HWT 9-10 (time, karma,...)

6 13 H1-Nat, Pythagoras; Emma-Hobbes. H2-Katelin, Machiavelli. H3-Shelby-Hobbes; Silas-Machiavelli

- Machiavelli (see LHP)

- Hobbes (see LHP)

- Something discussed in FL 11-12 (magical thinking, miracle cures, pseudoscience, get-rich-quick schemes,...) or HWT 11-13 (Japanese minimalism, Buddhism, naturalism, Taoism, unity in Islam,...)

15 H1-Mera, Descartes; Carly, early conspiracy theories. H2-Eliah, Descartes. Archer, early conspiracy theories. H3-Tessa, Descartes

- Montaigne (see Weiner 14)

- Descartes (see LHP)

- Something discussed in FL 13-14 (early conspiracy theories, civil war & secession fantasies,...)

- Something discussed in HWT 14-15 (scientific reductionism,...)

20 H1-Jocelyn, Buddhism and the self; Jake-Spinoza. H2-Keira, Suburban fantasies; JT-Locke. H3-Kendal, FL 15-16

- Spinoza (see LHP)

- Locke (see LHP)

- Something discussed in FL 15-16 (pastoral & suburban fantasies, P.T. Barnum, snake oil,...) or HWT 16-17 (Buddhism and the self,...)

22 H1-Jackson, Mill; Grace-Leibniz. H2-Nicholas, Rousseau

- Leibniz (see LHP)

- Hume (see LHP)

- Rousseau (see LHP, Weiner 3 & WGU...)

27 H1-Ani, Kant; Allison-Hegel. H2-Spencer, Kant.

- Kant (see LHP)

- Hegel(see LHP)

- Schopenhauer (see LHP & Weiner 5)

29 H1-Jaylin, Darwin; Madison, Marx. H3-Aj, Marx; Dyauni, Darwin. NOTE: This is exam day, we'll have reports if time allows. Otherwise, we'll do these after Spring Break. Or, we can double up on the 27th.

- Mill (see LHP)

- Darwin (see LHP & FL 18, with particular attention to the Scopes Trial)

- Kierkegaard (see LHP)

- Marx (see LHP)

"Why do we work so hard /To get what we don’t even want?"

Nice epicurean message here...

The day is short The night is long Why do we work so hard To get what we don’t even want? We work so hard to get ahead of the game Work half our lives until we’ve won. And then one day we sit on the edge of our bed And we think, “Lord, what have I done?” The day is short The night is long Why do we work so hard To get what you don’t even want? The man in the suit comes home and kisses his babies goodbye. “Daddy’s got to go on a trip, honey, oh no, don’t you cry.” He’s gone for a week then he’s home for a day. Well, pretty soon the babies won’t cry when Daddy’s gone away. The day is short The night is long Why do you work so hard To get what you don’t even want? You know we go to the mall and we go from store to store. Everybody seems to be wasting time until death walks through the door. And then you look at all your merchandise and you see We paid too high a price, you’ll see The day is short The night is long Why do we work so hard To get what you don’t even want

Celebrating the fortuitous swerve of existence

"Epicurus was no hedonist. He was a “tranquillist.”

Some psychologists take exception with Epicurus’s focus almost exclusively on pain relief. “Happiness is definitely something other than the mere absence of all pain,” sniffs the Journal of Happiness Studies.

Before reading Epicurus, I would have agreed. Now I’m not so sure. If I’m honest with myself, I recognize that what I crave most is not fame or wealth but peace of mind, the “pure pleasure of existing.” It’s nearly impossible to describe such a state in terms other than that of absence.

Avoiding pain is sound advice—I’m all for it—but isn’t it an awfully thin basis for a philosophy? Not if you’re in pain, Epicurus thought. Imagine you’ve fallen from a horse and broken your leg. A doctor is summoned and promptly offers you a bowl of grapes. What’s wrong? The grapes are pleasurable, aren’t they?

This absurd situation is the one many of us find ourselves in, Epicurus believed. We scoop trivial pleasures atop a mountain of pain, and wonder why we’re not happy. Some of us suffer the sharp shock of physical pain, others the dull ache of mental pain or the I want-to-die pain of a broken heart, but pain is pain, and we must address it if we hope to achieve contentment.

“We are only born once—twice is not allowed,” he said. Every human life, Epicurus believed, is the fortuitous product of chance, a swerve in atomic motion, a miracle of sorts. Shouldn’t we celebrate that?"

"The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers" by Eric Weiner: https://a.co/g3mFh61

Epicurus on death and “the most savory dish, the most agreeable moments”

"… a correct comprehension of the fact that death means nothing to us makes the mortal aspect of life pleasurable, not by conferring on us a boundless period of time but by removing the yearning for deathlessness. …

This, the most horrifying of evils, means nothing to us, then, because so long as we are existent death is not present and whenever it is present we are nonexistent. …

The sophisticated person neither begs off from living nor dreads not living. …

As in the case of food he prefers the most savory dish to merely the larger portion, so in the case of time he garners to himself the most agreeable moments rather than the longest span…"

https://open.substack.com/pub/figsinwinter/p/epicurus-on-death-and-the-gods?r=35ogp&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Gertrude and WJ

"It's the birthday of the avant-garde novelist and poet Gertrude Stein, born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (1874). She was one of the early students at Radcliffe College, the sister school to Harvard University, and her favorite professor was the psychologist William James. He taught her that language often tricks us into thinking in particular ways and along particular lines. As a way of breaking free of language, he suggested she try something called automatic writing: a method of writing down as quickly as she could whatever came into her head. She loved it, and used it as one of her writing methods for the rest of her life."

https://open.substack.com/pub/thewritersalmanac/p/the-writers-almanac-from-saturday-942?r=35ogp&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Friday, February 2, 2024

Philosophy tutor, Writing Center

The tutor for this year is Elle Robinson. Her email address, should you need to contact her, is:

ljr3s@mtmail.mtsu.edu ...

Her hours will be Mondays & Wednesdays, 6 pm until 7:45 pm, Feb 19--Apr 24. She will offer tutoring in the library.

No tutoring will be offered during Spring Break.

==

WRITING CENTER: The Margaret H. Ordoubadian University Writing Center is located in LIB 362 and online at www.mtsu.edu/writing-center. Here, students can receive valuable (and FREE!) one-to-one assistance in person or online on writing projects for any course. Please make your appointment by stopping by LIB 362, calling 615-904-8237, or visiting the UWC website. Visit early and often!

https://www.mtsu.edu/writing-center/

Don’t make it deeper

"I despise the kind of book which tells you how to live, how to make yourself happy. Philosophers have no good news for you at this level. I believe the first duty of philosophy is making you understand what deep shit you are in!" Slavoj Zizek

THREE ROADS TO TRANQUILITY

ARISTOTLE DIED ONE YEAR AFTER HIS FORMER PUPIL, ALEXANDER the Great. By common convention, Alexander's death in 323 BC marks the start of a new era in ancient history, the 'Hellenistic age', which has a convenient terminus nearly 300 years later with the picturesque death of Cleopatra, the Roman annexation of Egypt and the rise of a new empire as Greece gave way to Rome. Alexander's achievement had been to carry Greek culture into far-flung territories in a ten-year rampage south to Egypt and east to India. After his death, leaving no clear successor to run an empire that had anyway been too quickly assembled to stay in one piece, the newly enlarged Greek-speaking world became a patchwork of monarchies ruled by Alexander's former generals (Cleopatra was the last ruler of the dynasty established by Ptolemy Soter, one of Alexander's generals in Egypt). Now that it was spread thinly over a wide area, Greek culture inevitably became diluted in a soup of foreign ideas and religions. Alexander's former domain became a Hellenistic world rather than a Hellenic one—that is to say, it was Greek-ish rather than purely Greek. Athens ceased to be the centre of the intellectual map, as Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch in Syria, Pergamon in Asia Minor and later Rhodes in the eastern Aegean became rival centres of learning. Athens remained unchallenged as the capital of philosophy until well into Christian times. But philosophy itself was changing; it had a wider, more cosmopolitan audience to satisfy. The Hellenistic period brought a new era in philosophy as well as in general history.

It was in those days that Western philosophy came to be seen as above all a guide to life and a source of comfort:

"Empty are the words of that philosopher who offers no therapy for human suffering. For just as there is no use in medical expertise if it does not give therapy for bodily diseases, so too there is no use in philosophy if it does not expel the suffering of the soul."

So said Epicurus (341–271 BC), the most famous of the new Hellenistic philosophers, and on this point he spoke for all of them. There were three main new schools of thought: the Epicureans, the Stoics and the Sceptics. On the whole, if an Epicurean said one thing, a Stoic would say the opposite and a Sceptic would refuse to commit himself either way. But there was something about which they could all agree: philosophy was a therapeutic art, not just an idle pastime for people who were too clever by half.

Epicureanism and Stoicism were to some extent popular creeds in a way that the drier teachings of Plato and Aristotle could never be. The Platonic and Aristotelian schools continued to exist in one form or another throughout the Hellenistic period, doing research and teaching an elite. They certainly had something to say about how one should live, but not perhaps much that could readily be understood and even applied by the ordinary man in the market-place. By contrast, many of the new Hellenistic philosophers were keen popularizers…

The new schools of thought owed more to Socrates than they did to Plato or Aristotle. It was Socrates who had stressed the practical relevance of philosophy. Its point, he urged, was to change your priorities and thereby your life. The Hellenistic philosophies tried to deliver on this Socratic promise. In particular, they claimed to be able to produce the sort of peace of mind and tranquil assurance that Socrates himself had conspicuously possessed."

— Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance by Anthony Gottlieb

https://a.co/eiPYB2m

Th search goes on

Bertrand Russell, who died on this day in 1970

https://www.threads.net/@reboomer/post/C22BnHQL_t0/

Me too.

Thursday, February 1, 2024

Religious Studies Colloquium - Capitalism as Moral Code - Feb 15

We are excited to announce the Spring 2024 Religious Studies Colloquium Speaker will be Dr. Jeremy Posadas (Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Gender Studies, Stetson University). Dr. Posadas will speak on the topic “Capitalism as Moral Code” on Thursday, February 15, 2024, at 4:30 PM in the Academic Classroom Building, Room 106.

Dr. Posadas is a nationally renowned scholar in the field of religious studies. As a social ethicist, his work critiques unjust aspects of society and proposes alternatives to promote social justice on the basis of inter-sectionally feminist, queer, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and eco-centric moral principles.

Too much s(c/k)epticism

We're scheduled to discuss Pyrrhonian skepticism today in CoPhi, and we're meeting in the library. Really. It doesn't just seem so.

(Pyrrho seems to me a lot like Douglas Adams's "ruler of the universe"--"I say what it occurs to me to say when I hear people say things. More I cannot say..."…)

"All sorts of philosophers from Aristotle to David Hume ["a wise man proportions his belief to the evidence"] have argued that too much scepticism makes life impossible...

Questions FEB 1

Remember, we meet in the Library (Room 264A) today with librarian Rachel Kirk. Bring your questions about navigating the library and its website.

Skepticism-LH 3. FL 5-6, HWT 4-5.

"Skepticism is the first step toward truth."

- Denis Diderot

Diderot, born #onthisday in 1713, is probably best known for editing the "Encyclopédie" - the 'dictionary of human knowledge'.

Find here Diderot's Wikipedia entry (oh irony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denis_Diderot

Learn more in a 1.5 minute video about this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C71vkrsiyKE

Pyrrho

Pyrrho was the starting-point for a philosophical movement known as Pyrrhonism that flourished beginning several centuries after his own time. This later Pyrrhonism was one of the two major traditions of sceptical thought in the Greco-Roman world (the other being located in Plato’s Academy during much of the Hellenistic period). Perhaps the central question about Pyrrho is whether or to what extent he himself was a sceptic in the later Pyrrhonist mold. The later Pyrrhonists claimed inspiration from him; and, as we shall see, there is undeniably some basis for this. But it does not follow that Pyrrho’s philosophy was identical to that of this later movement, or even that the later Pyrrhonists thought that it was identical; the claims of indebtedness that are expressed by or attributed to members of the later Pyrrhonist tradition are broad and general in character (and in Sextus Empiricus’ case notably cautious—see Outlines of Pyrrhonism 1.7), and do not in themselves point to any particular reconstruction of Pyrrho’s thought. It is necessary, therefore, to focus on the meager evidence bearing explicitly upon Pyrrho’s own ideas and attitudes. How we read this evidence will also, of course, affect our conception of Pyrrho’s relations with his own philosophical contemporaries and predecessors... (Stanford Encyclopedia, continues)

==

Pyrrho not an idiot

"Pyrrho ignored all the apparent dangers of the world because he questioned whether they really were dangers, ‘avoiding nothing and taking no precautions, facing everything as it came, wagons, precipices, dogs’. Luckily he was always accompanied by friends who could not quite manage the same enviable lack of concern and so took care of him, pulling him out of the way of oncoming traffic and so on. They must have had a hard job of it, because ‘often . . . he would leave his home and, telling no one, would go roaming about with whomsoever he chanced to meet’.

Two centuries after Pyrrho’s death, one of his defenders tossed aside these tales and claimed that ‘although he practised philosophy on the principles of suspension of judgement, he did not act carelessly in the details of everyday life’. This must be right. Pyrrho may have been magnificently imperturbable—Epicurus was said to have admired him on this account, and another fan marvelled at the way he had apparently ‘unloosed the shackles of every deception and persuasion’. But he was surely not an idiot. He apparently lived to be nearly ninety, which would have been unlikely if the stories of his recklessness had been true."

"The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance by Anthony Gottlieb -- a very good history of western philosophy.

==

A character in Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, identified as The Ruler of the Universe, has been called a solipsist. I think he sounds more like a Pyrrhonian skeptic... "I say what it occurs to me to say when I hear people say things. More I cannot say..."

What the world needs now

— Bertrand Russell

https://www.threads.net/@philosophybits/post/C2xkEwhv1Qc/

Readers think

(Book: Palm Sunday [ad] https://amzn.to/3Od92Zg)

https://www.threads.net/@philo.thoughts/post/C2zRs0TiKMq/

Needleman on meaning & time

Time and the soul – philosopher Jacob Needleman on our search for meaning https://www.themarginalian.org/2024/01/30/time-and-the-soul-needleman/

https://www.threads.net/@mariapopova/post/C2xNQ0wuvzQ/