LISTEN. I was saying in class yesterday that my preferred approach to class prep these days is to rise early and try to come up with something fresh and novel to say about the philosopher(s) du jour. So, what's new with Socrates and Plato?

Well, according to Xenephon, Plato's Socrates is "pure rationality" whereas the real Socrates was a dispenser of practical "how to live" advice... (continues)

==

Trial of Socrates (399 B.C.)

The trial and execution of of Socrates in Athens in 399 B.C.E. puzzles historians. Why, in a society enjoying more freedom and democracy than any the world had ever seen, would a seventy-year-old philosopher be put to death for what he was teaching? The puzzle is all the greater because Socrates had taught--without molestation--all of his adult life. What could Socrates have said or done than prompted a jury of 500 Athenians to send him to his death just a few years before he would have died naturally? (continues)

==

Xenophon (430—354 B.C.E.)

Xenophon was a Greek philosopher, soldier, historian, memoirist, and the author of numerous practical treatises on subjects ranging from horsemanship to taxation. While best known in the contemporary philosophical world as the author of a series of sketches of Socrates in conversation, known by their Latin title Memorabilia, Xenophon also wrote a Symposium and an Apology which present a set of vivid and intriguing portraits of Socrates and display some sharp contrasts to the better known portraits in the works of Xenophon’s contemporary, Plato. Xenophon’s influence in Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and in Early Modern intellectual circles was considerable; he was a pioneer in several literary genres including the first-person military memoir (Anabasis) , the biographical novel (Education of Cyrus), and the continued history (Hellenica). The range of his areas of expertise and the glancing charm of his down-to-earth writing style continue to fascinate and repay our study. For one example of his work in moral philosophy, he emphasized the importance of self-control, which comprises one of the cardinal virtues of Greek popular morality. This is highlighted by Xenophon in many ways. Socrates is often said by Xenophon to have exemplified it in the very highest degree. Cyrus displays it when he is invited to look upon the most beautiful woman in Asia, who happens to be his prisoner of war. He firmly declines this temptation; but his general Araspas stares at her endlessly, falls in lust, insults her honor, and ignites a chain of events described by Xenophon that ends in her suicide over her husband’s corpse... (continues)

==

Did Comedy Kill Socrates?

Comedy can just as easily be populist — on the side of the majority, and against individuals or groups who don’t fit in or conform. A fascinating early test-case of such issues is Aristophanes’ play The Clouds, staged in 423 BC, in which the philosopher Socrates is presented as a remote, haughty figure who repudiates normal Greek religion, worships private deities of his own, and runs a special school (the Thinking Institute) in which ideas subversive of traditional morality are taught. Is Clouds, then, a maliciously anti-intellectual comedy? Might it even have contributed to popular hostility against Socrates and the shattering fact of his execution in 399 BC on charges of rejecting the city’s gods and corrupting the young. Can comedy really be that powerful?

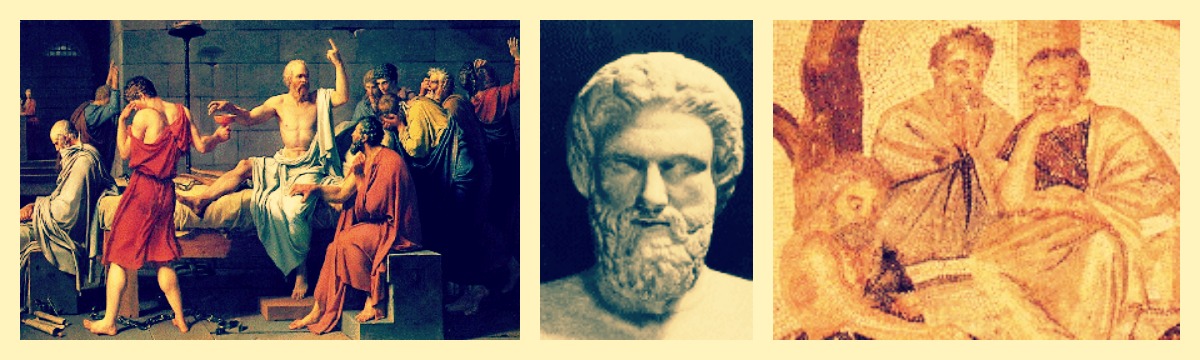

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Philip-Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762.

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Philip-Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762. Two things in particular have conspired to give these questions a disturbing historical edge. The first is that the surviving version of Clouds ends with the burning down of Socrates’ school (including, so some have supposed, the ‘death’ of Socrates and his pupils) by a disgruntled Athenian who thinks he has been cheated by Socrates: an incitement to violence against dangerous intellectuals, some critics of the play have believed. The second is a notorious passage in Plato’s Apology, a fictionalised version of Socrates’ defence speech at his trial, where the philosopher claims that his slanderers are too numerous to name – ‘unless one of them happens to be a comic poet’. Later in the Apology, Socrates refers explicitly to Clouds as a work which represents him ‘spouting a lot of nonsense on matters about which I know nothing whatsoever’. So we have a document written soon after Socrates’ lifetime’that tells us that Clouds had contributed to the hostile, anti-intellectual prejudices that led to the death of Socrates. Or do we? (continues)

The best books on Socrates

recommended by M M McCabe

The classical Greek philosopher is credited with laying the foundation of Western philosophy – without ever having written a word. Here, the eminent scholar M M McCabe recommends the best books to read to understand Socrates and engage with the eternal question: How best to live? (continues)

No comments:

Post a Comment