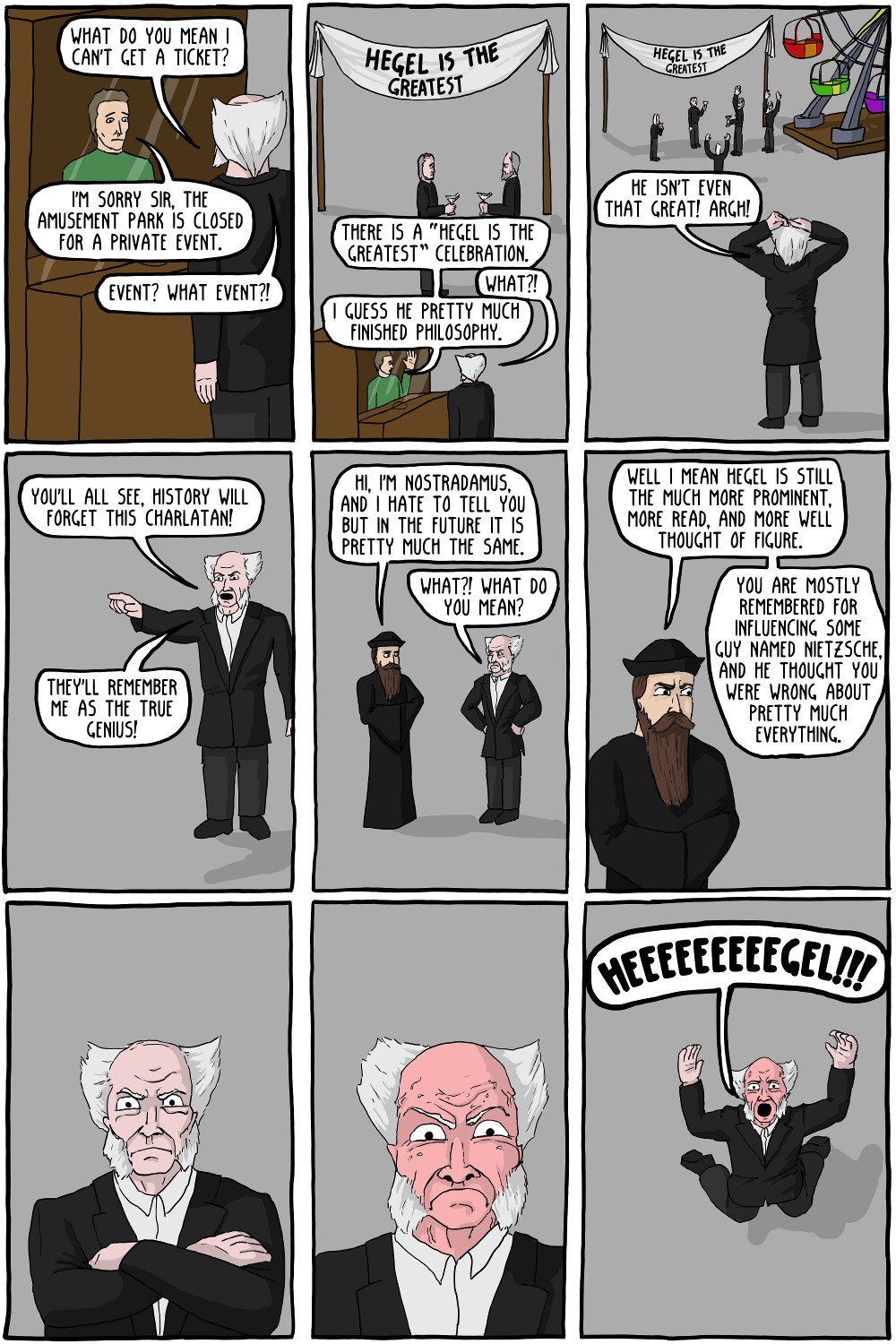

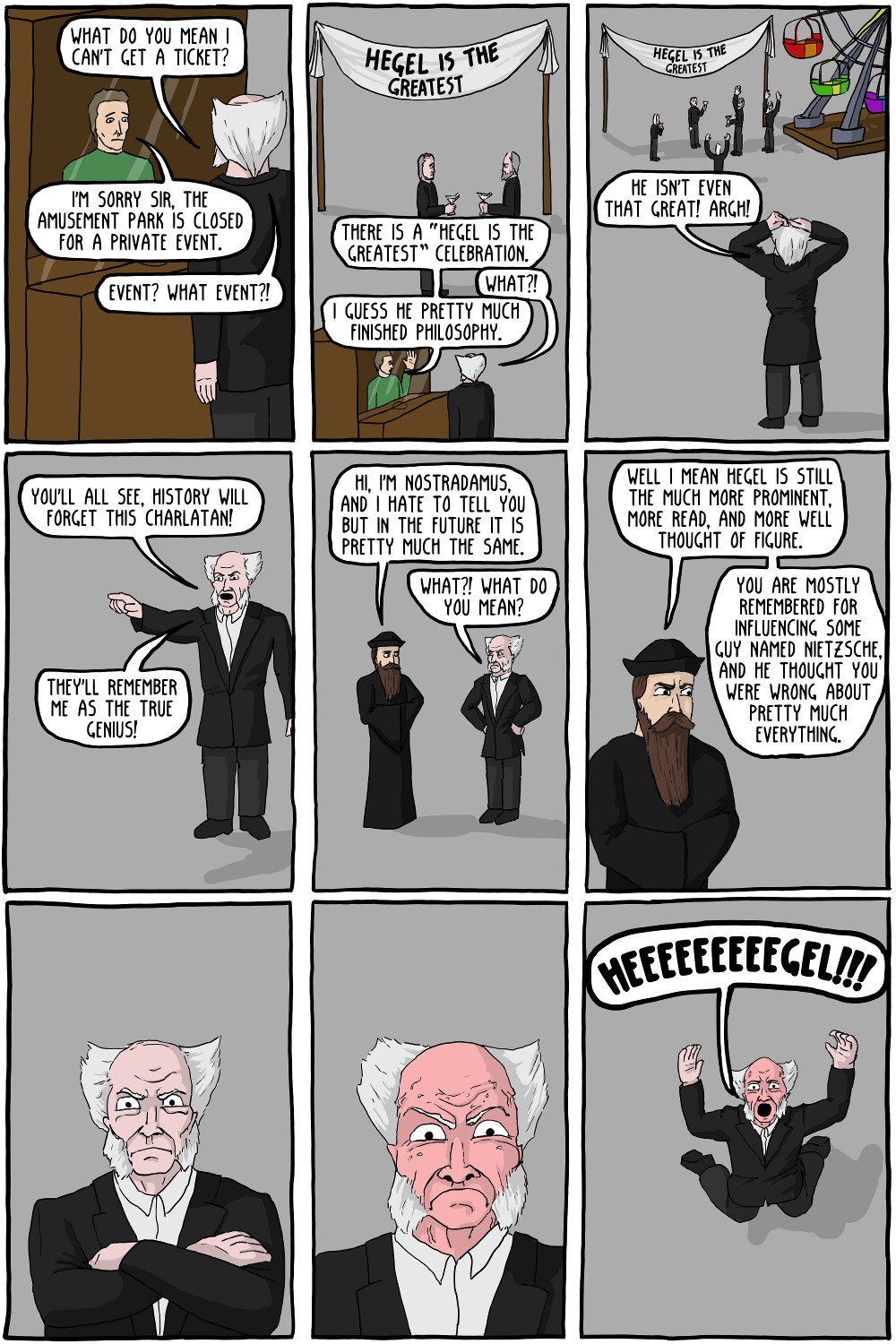

Following up Jay's Hegel report yesterday in section #13:

"A few examples of Hegel's dialectic method may serve to make it more intelligible. He begins the argument of his logic by the assumption that "the Absolute is Pure Being"; we assume that it just is, without assigning any qualities to it. But pure being without any qualities is nothing; therefore we are led to the antithesis: "The Absolute is Nothing." From this thesis and antithesis we pass on to the synthesis: The union of Being and Not-Being is Becoming, and so we say: "The Absolute is Becoming." This also, of course, won't do, because there has to be something that becomes. In this way our views of Reality develop by the continual correction of previous errors, all of which arose from undue abstraction, by taking something finite or limited as if it could be the whole. "The limitations of the finite do not come merely from without; its own nature is the cause of its abrogation, and by its own act it passes into its counterpart."

The process, according to Hegel, is essential to the understanding of the result. Each later stage of the dialectic contains all the earlier stages, as it were in solution; none of them is wholly superseded, but is given its proper place as a moment in the Whole. It is therefore impossible to reach the truth except by going through all the steps of the dialectic.

Knowledge as a whole has its triadic movement. It begins with sense perception, in which there is only awareness of the object. Then, through sceptical criticism of the senses, it becomes purely subjective. At last, it reaches the stage of self-knowledge, in which subject and object are no longer distinct. Thus self-consciousness is the highest form of knowledge. This, of course, must be the case in Hegel's system, for the highest kind of knowledge must be that possessed by the Absolute, and as the Absolute is the Whole there is nothing outside itself for it to know. In the best thinking, according to Hegel, thoughts become fluent and interfuse. Truth and falsehood are not sharply defined opposites, as is commonly supposed; nothing is wholly false, and nothing that we can know is wholly true. "We can know in a way that is false"; this happens when we attribute absolute truth to some detached piece of information. Such a question as "Where was Caesar born?" has a straightforward answer, which is true in a sense, but not in the philosophical sense. For philosophy, "the truth is the whole," and nothing partial is quite true.

"Reason," Hegel says, "is the conscious certainty of being all reality." This does not mean that a separate person is all reality; in his separateness he is not quite real, but what is real in him is his participation in Reality as a whole. In proportion as we become more rational, this participation is increased.

The Absolute Idea, with which the Logic ends, is something like Aristotle's God. It is thought thinking about itself. Clearly the Absolute cannot think about anything but itself, since there is nothing else, except to our partial and erroneous ways of apprehending Reality. We are told that Spirit is the only reality, and that its thought is reflected into itself by self-consciousness. The actual words in which the Absolute Idea is defined are very obscure. Wallace translates them as follows:

" The Absolute Idea. The Idea, as unity of the Subjective and Objective Idea, is the notion of the Idea--a notion whose object (Gegenstand) is the Idea as such, and for which the objective (Objekt) is Idea--an Object which embraces all characteristics in its unity." The original German is even more difficult. * The essence of the matter is, however, somewhat less complicated than Hegel makes it seem. The Absolute Idea is pure thought thinking about pure thought. This is all that God does throughout the ages--truly a Professor's God. Hegel goes on to say: "This unity is consequently the absolute and all truth, the Idea which thinks itself."

I come now to a singular feature of Hegel's philosophy, which distinguishes it from the philosophy of Plato or Plotinus or Spinoza. Although ultimate reality is timeless, and time is merely an illusion generated by our inability to see the Whole, yet the time-process has an intimate relation to the purely logical process of the dialectic. World history, in fact, has advanced through the categories, from Pure Being in China (of which Hegel knew nothing except that it was) to the Absolute Idea, which seems to have been nearly, if not quite, realized in the Prussian State. I cannot see any justification, on the basis of his own metaphysic, for the view that world history repeats the transitions of the dialectic, yet that is the thesis which he developed in his Philosophy of History. It was an interesting thesis, giving unity and meaning to the revolutions of human affairs. Like other historical theories, it required, if it was to be made plausible, some distortion of facts and considerable ignorance. Hegel, like Marx and Spengler after him, possessed both these qualifications. It is odd that a process which is represented as cosmic should all have taken place on our planet, and most of it near the Mediterranean. Nor is there any reason, if reality is timeless, why the later parts of the process should embody higher categories than the earlier parts unless one were to adopt the blasphemous supposition that the Universe was gradually learning Hegel's philosophy…"

— A History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell

As someone who spent so long reading over hegel and schopenhauer I really appreciate this comic!

ReplyDelete